Case Study:

Tierra Nueva

A new local perspective

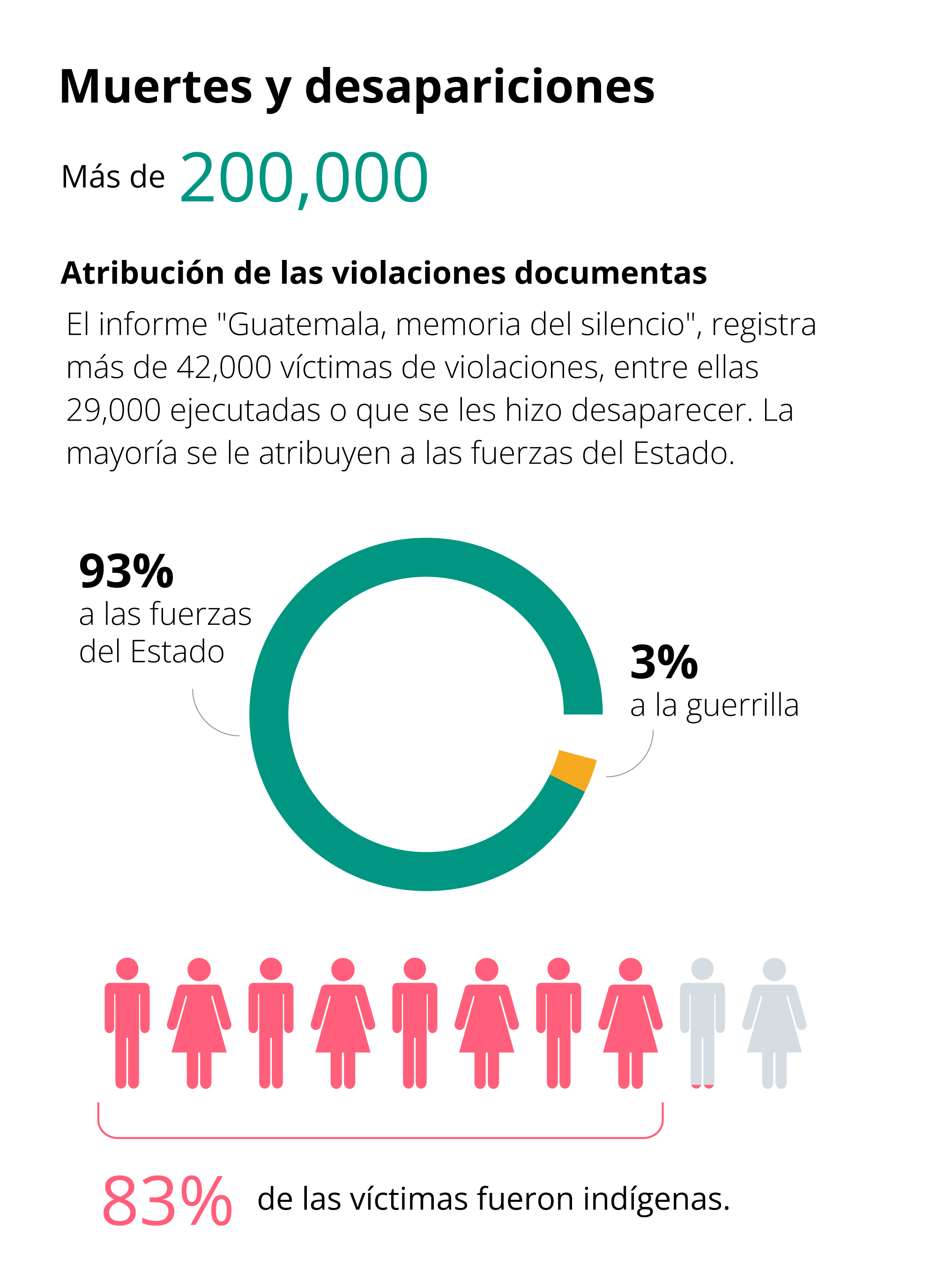

Guatemala had been engulfed in a civil war since 1960. Within the government, the most extreme way to attack and annihilate the guerrilla forces was devised: disarm them from their very civilian and citizen bases. Thus, counterinsurgency policies became a weapon against the citizenry and particularly against indigenous peoples.

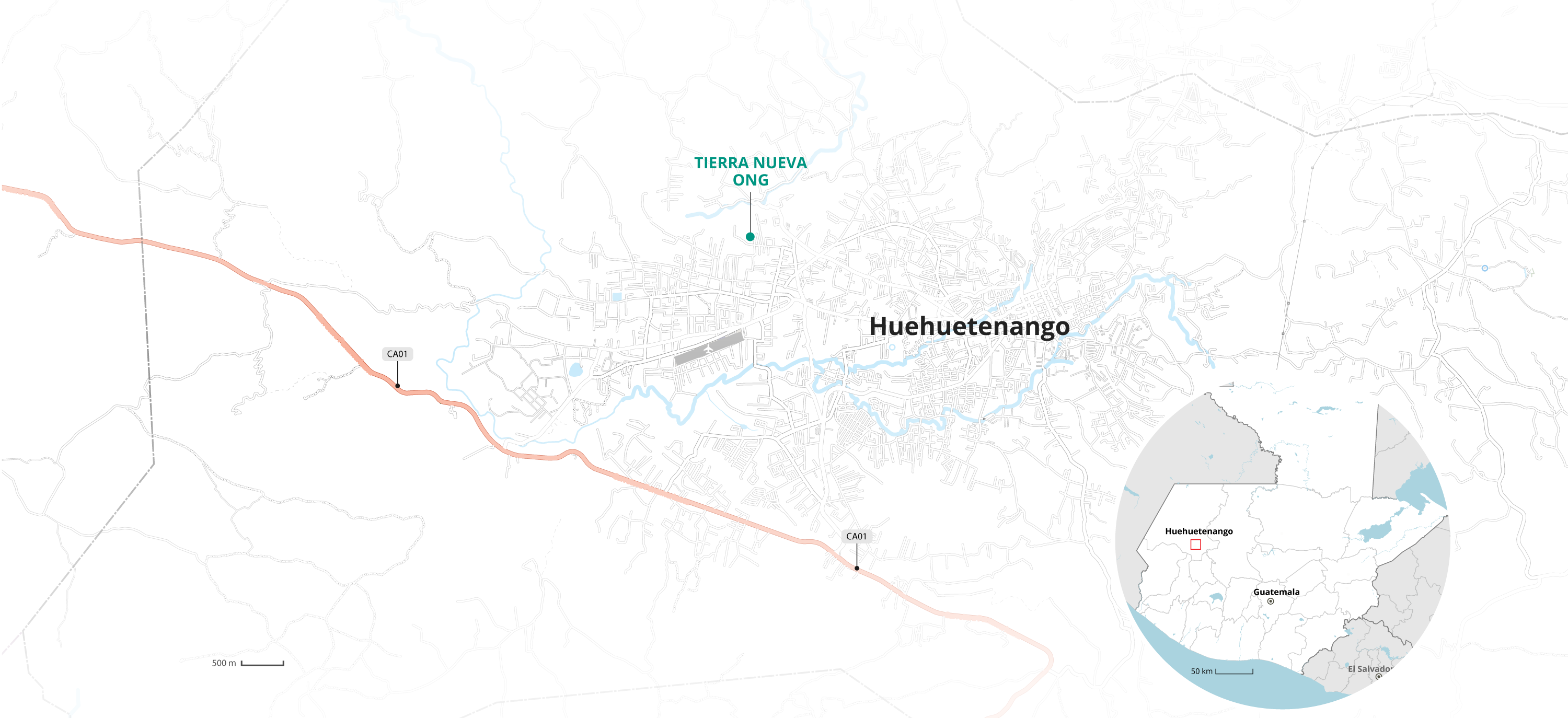

Huehuetenango is a historically multiethnic and border department. Therefore, diversity and movement are part of the territory's idiosyncrasy. However, in the civil war, these aspects took on another meaning.

The department was not free from the violence and repression of that era. The military state massacred rural communities. In the multiethnic context of Huehuetenango, the massacres acquired a particular nuance. According to the Historical Clarification Commission (CEH), 83% of the victims of the civil war were indigenous. Therefore, the state's counterinsurgency policies were simultaneously a policy of genocide against indigenous peoples.

On the other hand, state violence forced numerous families from Huehuetenango into exile or hiding. The forced displacement of these populations led them to take refuge in Mexico and the United States, or to hide in the hills that have guarded Huehuetenango lands for centuries.

Nevertheless, it was a war that, according to the CEH, left more than 200,000 victims, dead and disappeared, and more than one and a half million people displaced.

However, in 1996, after 36 long and bloody years, the Peace Accords were signed in the capital city, which would cease the fire and conflicts between the State and the guerrilla. However, far from the capital, peace would not represent a major material change or the apex of a promise of a renewed state role in the development of a new society. It was an official peace.

At the dawn of the new millennium, Huehuetenango was stirring from within. On the one hand, the official peace triggered new migrations: those returning from exile and hiding, who joined the war survivors who remained in the department. People whose lives were marked by emotional trauma, economic precariousness, and the communal dispossession of war.

Especially the youth and children that the returning families carried from exile or, in more regrettable cases, who were in absolute orphanhood. A youth, a childhood without opportunities and uprooted.

On the other hand, the Peace Accords turned out to be an opening to international focus and aid for the country. Thus, Guatemala received inflows of foreign projects and funding aimed at fulfilling much of what was stipulated in the Accords.

For Huehuetenango, this phenomenon was not strange. Ambitious projects by the European Union and international cooperation were notable in the early 2000s, whose main theme was economic development.

In those early years, a small vibration occurred among all the agitation and movement boiling in Huehuetenango, which anyone would have passed as imperceptible. It was 2002, and a group of Huehuetenango professionals from various fields, along with colleagues, clearly identified the context in which the department found itself.

From discussions and analysis held in meetings in the living rooms of their homes, the group observed the potential of the new projects in Huehuetenango. However, they questioned whether these international initiatives, bringing foreign staff to implement foreign proposals in a territory that was not their own, truly met local needs or employed Huehuetenango professionals. They further disputed the nature of these projects, since they did not deeply understand local needs nor employ local professionals.

Another point they objected to was the focus of the projects. Framed and entrenched in economic development, the international initiatives fell short of the group's common vision: human development.

The group was young. Therefore, education was especially important. They were young adults who understood the situation of the youth in the city of Huehuetenango and, even more so, in the most remote and forgotten villages. Additionally, the migrations of returnees and the camps of refugees from the war were full of young people who found themselves in lands stripped of services, including education.

Faced with this context, the group decided to found an organization that would broaden the existing development approach, incorporate local people who knew Huehuetenango well, and prioritize youth. An organization that would represent a local bet over official peace and international developmentalism.

Thus was born Tierra Nueva.

The director of Tierra Nueva NGO, Álvaro Gómez, about the work of the organization, the importance of post-pandemic educational recovery through the initiative Recovering Education in Central America: Activating Networks and Associated Groups (RECARGA) and the experience with the study of case guided by Population Council Guatemala.

A historical context of Huehuetenango

Before delving into the story of Tierra Nueva, it is necessary to understand the historical context of Huehuetenango. Its history outlines how the department has been characterized especially by its ethnic richness and its border quality, and the sorrows it has suffered to the detriment of these historical aspects.

Huehuetenango before the 20th century

Currently, Huehuetenango is located in the northwest of Guatemala. The department consists of 32 municipalities. It is characterized as a multiethnic region where Mam, Q'anjob'al, K'iche', Jakalteko/Popti', Akateko, Chuj, Chalchiteka, and Awakateka populations reside. Around 65.2% of the population identifies as Maya.

The multiethnic diversity of Huehuetenango dates back to the pre-Hispanic period1, as it has been inhabited by indigenous populations since then. It was a strategic region for ancient Mesoamerica, as it functioned as a communication and transit bridge between the south and north. Therefore, it has historically been a territory of border, migration, and movement that was commercially and politically leveraged by the pre-Hispanic lordships of Huehuetenango.

With the processes of invasion and Spanish colonization starting in 1492, multiple changes were introduced in the settlement patterns (the reductions of Indians), a new power dynamic (indigenous slavery), and a different system of justice and governance (pigmentocracy). Spanish colonization with military force and evangelization irremediably fractured and transformed the cultural, social, and political life of the pre-Hispanic peoples2.

It was not until 1866, in the liberal period, that Huehuetenango was officially established as a department. At that time, the establishment of an agro-export economic model state brought about a series of changes that would negatively impact the indigenous population of the department. Access to and control over land for the indigenous population were limited in the face of dispossession and privatization processes that fueled much conflict, violence, and repression.

Huehuetenango during the Civil War

In the 20th century, one of the most decisive events for Huehuetenango was the civil war.

The Guerrilla Army of the Poor reached the department in the mid-1970s and began the first contacts with the population. Over the years, they would extend throughout the department, but guerrilla actions intensified in the early '80s. Additionally, the state's abandonment and the presence of religious orders fostered community organization and political awareness among the population.

In response to these dynamics, the military state, particularly under the authoritarian governments of Romeo Lucas García and Efraín Ríos Montt, responded with violent and repressive counterinsurgency strategies. The military identified the civilian population as a target to be dismantled and neutralized. As a result, Huehuetenango became the grim scene of several massacres, including those in the farms of San Francisco Nentón, Santa Cruz Barillas, and San Mateo Ixtatán.

The atrocious violence of the armed conflict was a reason for displacement for the population of Huehuetenango. Many inhabitants decided to seek refuge in Mexico or the United States, as well as migrate to other parts of the country.

Huehuetenengo in the 21st century

The presence of the state in the department of Huehuetenango has been quite limited, not to forget that for much of the 20th century, state action has been policies of repression and extermination when it has indeed been present. Additionally, being in an isolated area, government interference has been practically non-existent.

Due to this general poverty in many parts of the department, Huehuetenango has become one of the main areas that expels migrants and one of the departments with the highest reception of remittances nationally. Migration has become an alternative for many families in the region to access economic and job opportunities. Remittances have also become a fundamental source for the sustenance of families and communities, generally invested in housing, clothing, food, health, and education.

Alongside Totonicapán and Alta Verapaz (departments, incidentally, with an indigenous majority), Huehuetenango has some of the worst indices in terms of education, teenage pregnancies, early unions, and child migration. This situation is reflected in school access, especially at the secondary and diversified levels, the technological infrastructure required for teaching, and school dropout. Thus, poverty, the lack of state presence, and migration have been profound afflictions that have affected education.

A New Land in Huehuetenango

In 2005, Tierra Nueva was legally registered as a non-governmental organization (NGO)3. Despite good intentions and exciting expectations to start different and influential work in Huehuetenango, the organization's early years were difficult. A first period that over time remained as a distant memory now contrasts with the notable trajectory that Tierra Nueva has demonstrated4.

Difficult beginnings

The co-founders of Tierra Nueva remember that “we had to go door to door” to get any hope, however small, of funding. Contacts, approaches with authorities, and donors to whom they presented their proposals and projects ended in disappointment. Nobody and nothing turned to look at this unknown and novice NGO except to offer them the same condescending phrase: "if you survive five years, look us up.”

Thus passed the first two years after the legalization of Tierra Nueva: knocking on doors that were instantly closed. Additionally, the team at that time was volunteer, driven by their dream and desire to get Tierra Nueva off the ground. With that fervent attitude, they finally won their first project.

In 2007, the European Union (EU) approved, to the joy and somewhat surprise of Tierra Nueva, their project on domestic violence. The co-founders recalled those distant years when they secured their first project:

"I think we are attractive as an organization. Our proposal was, and still is, appealing. What was proposed was something objective: that women could access judicial and psychological orientation. We bet on prevention, the importance of families living and coexisting well. We were a bargain; many actions with little resources: consultancies, legal and psychological orientation centers, training of community promoters, radio program, public address system. The actions were objective, concrete, and relatively economical."

At that time, Tierra Nueva coexisted with numerous other larger and more recognized organizations. However, the attractive proposals, the small and professional team, the wide range of considered actions from the projects, and above all, the constant effort not to give up in their search for support and financing were the perfect combination for the EU to believe in Tierra Nueva for four years.

Versatility and the start of growth

One of the distinguishing characteristics of Tierra Nueva is its versatility. From the beginning, they have considered developing proposals covered with diverse approaches and working on projects on different topics without overlooking the needs—some more urgent than others—of Huehuetenango, its communities, and its inhabitants. At the core of versatility lies the integral vision of the organization and the team. Thus, intricate needs of a complex territory require solutions and approaches that address the many involved aspects.

Initially, after founding the organization, they established a series of strategic areas. Originally, there were 12. As the co-founders now recognize, every nascent organization, amid the excitement and impulse, has a burst of ambition to solve the world. In the case of Tierra Nueva, to solve Huehuetenango.

We refer to this first strategic structure to verify the multifaceted extent of the professional activities of Tierra Nueva. In this line, they achieved in that first period new partners who kick-started a gradual growth.

In 2008, they linked up with the United Nations Program. The project consisted of promoting a public policy against racism and discrimination in virtue of addressing the aftermath of the civil war in Huehuetenango.

It was a fundamental and fruitful alliance for Tierra Nueva as it has been the only program that has intervened in the 31 municipalities of the department. Thanks to the mapping and fieldwork, they got to know even more closely the insides, geographies, and communities of their department. It was a base that would later serve them in the expansion of their work outside the municipality of Huehuetenango.

Two years later, they partnered with PCS in a human rights program in post-conflict countries. Tierra Nueva implemented a set of actions: circles of reflection on non-violence, Mayan languages, recovery of oral tradition, family dialogue. Furthermore, this project marks more emphatically one of the essential aspects of the organization's work: the production of materials.

"In Huehuetenango, there are nine linguistic communities. People speak it but do not read it. We produced materials in the languages, but they could not read them. If they understood it, we made that material. If not, the circles of reflection revolved around what they heard. It empowered youths from different municipalities to run radio programs about what was happening in their communities. Thus began the community spokespeople."

2010 was a pivotal year for Tierra Nueva as the two projects became solid bases for growth that continues to this day. On the other hand, they allied with Child Fund International (CFI), which would represent a watershed for the organization, especially in its educational work. Their alliance with CFI would be the clay with which they would mold their particular pedagogy.

The alternative pedagogy of Tierra Nueva

Tierra Nueva already had a recognized trajectory by 2010. That’s why CFI sought the organization to form an alliance. For Tierra Nueva, this association meant establishing a specific focus on education that had not previously existed with such force. To the point that now it is a programmatic area called Alternative Education, as it is fundamental in the organization’s current work.

The alliance with CFI has been vital for Tierra Nueva as it has represented a source of funding and resources that remains effective to this day. However, it has not been a one-way relationship. The Tierra Nueva team has adapted their ideas and methods to fit the structure of CFI. Likewise, constant communication—a give and take, as the team recognizes—with the donor has resulted in negotiations and adjustments that have allowed Tierra Nueva not to renounce its original vision.

The guidance and instruction from CFI led them to tailor their age group structures. However, it did not mean a literal or absolute adaptation. Rather, it was a foundation upon which they built their educational project with its own signature. Overall, Tierra Nueva has been the main protagonist in constructing its alternative pedagogy.

Educating childhood

The first group attended to by Tierra Nueva is infants aged 0 to 5 years. With this age group, they focus programs and activities on developing early stimulation and skills. The purpose is not only in the personal development of the infants, but also in preparing them for preschool education.

“They used to take us to be weighed, they had a center, they gave us medications, it was a health check. Then they took us to get trained to paint, something more playful. My mom told me that they used to let us play with toys, learn colors, motor skills. Later they took us to a place where we played with other little friends.”

In this initial age group, what stands out most is Tierra Nueva’s community turn. Without losing their principles of betting and strengthening the local, they work with mothers from the communities where the programs operate.

“We train guide mothers who are from the community. They are given a training process for the different levels of stimulation. Then they are the ones who will carry out the activity with the target mothers, as we call them, who are the mothers who already bring their children to the community stimulation centers. These community centers operate in different spaces. In the best cases in a classroom that is lent but it’s increasingly difficult. Another space has been community halls. But the most significant for us has been seeing families, especially women, realizing this benefit for their children. That’s why they have been giving us private homes, a corridor, or providing a small room where all the materials are stored. When the session is to be held, they take everything out to a large field and there the activities are developed.”

This community approach not only brought them closer to the communities to create a bond and trust with the program participants but also served a practical function. By training a group of guide mothers who later attend to a group of target mothers with one or more children, they strengthen the reach of the program through the community. According to the Tierra Nueva team, the community approach has managed to work with around 500 infants.

Educating children

The second group consists of children aged 6 to 14 years. Because they are at the schooling stage, Tierra Nueva centers its programs on mathematics and literacy. However, they carry the alternative stamp of Tierra Nueva. As for mathematics, the teaching is not limited to formal learning of mathematical content but also strengthens logical reasoning and critical thinking.

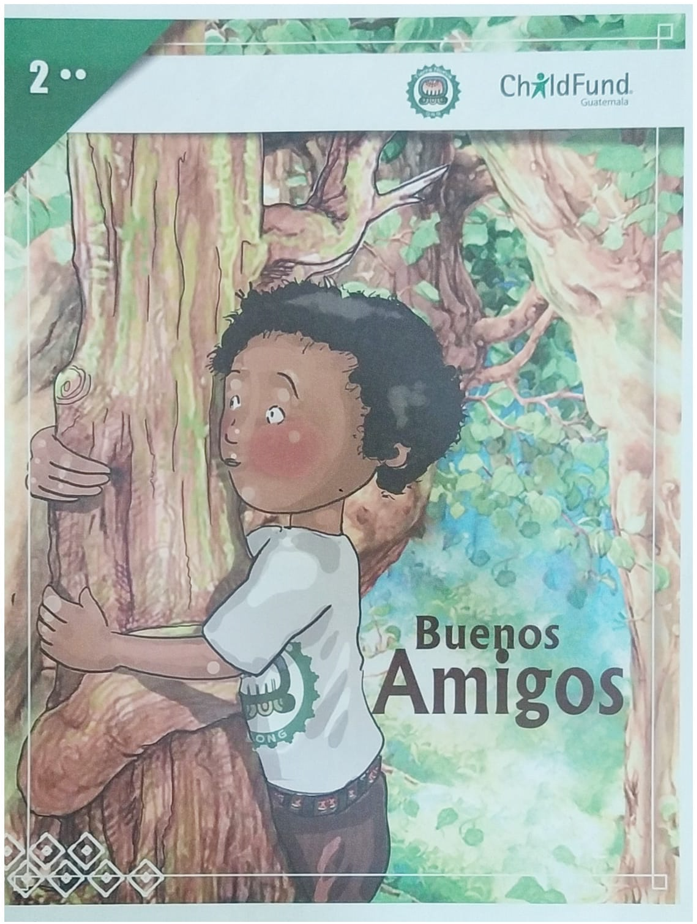

On the other hand, reading and writing are fundamental skills of teaching. Tierra Nueva’s literacy program promotes and exercises children to write their own stories. These texts are then collected in a book where they are illustrated and laid out. What is notable about this material production is giving children their creations, teaching them to read and write through a direct and participative role, and turning the texts into work and analysis tools for future use and for upcoming groups.

An example of the storybooks produced by Tierra Nueva. Courtesy of Tierra Nueva NGO.

An example of the storybooks produced by Tierra Nueva. Courtesy of Tierra Nueva NGO.

Alongside attention to children, Tierra Nueva did not forget the educators of its programs. They recognized that the alternative education of Tierra Nueva would eventually clash with the traditional education of the public and private system. Thus, with the intention of transmitting Tierra Nueva’s particular methodology and offering pedagogical openness to the teachers, they initiated diploma programs.

“The teachers were used to incentives. I would like to say that the adults got on the train, but many did not change the traditional chip of the teacher who sits, listens to me, and copies. There was also discrimination; teachers did not know the language. It was a stir to change ideologies: to tell the teacher, ‘you are not the center; the child is.’ Many teachers had the vocation, so it was beautiful to see how the tools allowed them to do new things in schools.”

Tierra Nueva called on professionals to train the organization’s staff in workshop themes and, above all, ludopedagogy, which has been a fundamental line in its alternative pedagogy. Play, expression, and experimentation are ways of teaching and learning. For Tierra Nueva, play opens education to knowledge that traditional teaching closes and scorns.

Play is present in programs and activities for infants, children, adolescents, and also in the training of the diploma programs for teachers. In the training, for example, they teach the bet on play to make reading and mathematics more comprehensible and friendly.

Educating adolescents

The third group consists of adolescents aged 15 to 24 years, particularly those outside the school system. Economic needs, parents prioritizing income over education, and overage are some reasons this population is external to or even excluded from the educational system. Thus, in Tierra Nueva, these adolescents are an urgent population to address, having few or no educational options.

The programs for this group have three lines of training: a) sexual and reproductive rights, b) positive and proactive citizenship, and c) labor training and entrepreneurship. These lines stem from the principles of self-realization, leadership, labor access, and community vision of Tierra Nueva.

Regarding positive and proactive citizenship, the goal is to raise adolescents' awareness of the importance of their community participation and involvement. Particularly for young people to be trained as leaders who resolve to transform their communities and their realities in an era where there is barely any. The adolescents of Huehuetenango are uprooted, particularly those in rural areas.

"They are young people from community areas of different Maya populations. Many of them with the perspective of 'I turn 15 and I'm off to the United States,' many with that mindset that they are not interested in what happens in our country. We now say 'all this political change that is happening [the events during and around the national elections of 2023], the young people are the ones who are really involved'—yes, the urban ones, but not the rural ones who just want to go earn money

In Tierra Nueva, they refuse to remain indifferent to this youth exodus through migration that will leave the department devoid of a generation capable of leading and transforming it.

On the other hand, in Tierra Nueva, it is fundamental to train adolescents in labor skills, knowledge, and especially rural adolescents. A rural young person will be at a disadvantage compared to an urban young person because the socioeconomic and material conditions of a village are more critical, precarious, and isolated than in the cities. For this reason, they have implemented programs to promote local entrepreneurship, instruct basic knowledge about labor requirements, and above all, teach technical education.

In this last regard, the Technical Training and Productivity Institute (INTECAP) has supported them. Tierra Nueva had space and coordination for the trainers that INTECAP sent to the communities. However, the process has been challenging. INTECAP built facilities in urban centers, making it impossible for rural youths to travel there.

The isolation of the communities has been a problem identified by Tierra Nueva from the beginning. Therefore, one of the notable and stellar projects with the idea of resolving that isolation, that distance, was the technological and human development centers.

Knowing that it was very difficult for young people from communities to travel to schools in urban centers, which made them decide to drop out of any desire or opportunity to study, in Tierra Nueva we resolved to “bring education to the young people.”

"The development centers had an impact in the communities. We started with a mobile unit equipped. The young people came, or we took them with our traveling bus, and they received training. We had promoters whom we trained on how to use the platform. Then they were in charge of attending. They received ICT modules, civic participation, and employability. Currently, they are still functioning in Chiantla, Aguacatán, Comintancillo. Young people who didn't know how to use a computer, who were afraid to use the mouse... By the end, they themselves used the equipment and removed the barrier."

The modules were developed by Tierra Nueva, as well as arranging the center for various uses such as printing and internet research. Overall, the centers were thought of as spaces for and by the community, sustainable by the trained promoters.

Lastly, for this age group, the alliance in 2022 with the General Directorate of Extracurricular Education (DIGEEX) of the Ministry of Education (MINEDUC) was key. Having established centers, educational platforms, and attention to youths excluded from the school system, Tierra Nueva decided strategically to associate with DIGEEX to expand educational services and include materials in their programs. Thus, DIGEEX handles the training, while Tierra Nueva provides the space and educators.

Tierra Nueva in Pandemic Times

Since 2010, Tierra Nueva entered a curve of institutional growth. Until now, we have placed education, especially the organization's alternative pedagogy, at the center. However, the work of Tierra Nueva extends to other themes and areas: violence prevention, migration, food security, social development, political empowerment, sexual and reproductive rights. This breadth has also translated into projects beyond Huehuetenango, in San Marcos and Totonicapán.

However, 2020 abruptly interrupted the rising dynamics of Tierra Nueva. Out of all forecasts and planning, no one in the organization was prepared to face a global phenomenon that locked down the entire world. The COVID-19 pandemic erupted.

En the midst of the pandemic

In the face of a global pandemic, particularly one that settled in so quickly without prior notice, any caution and reaction fell short. However, Tierra Nueva did not remain in paralysis that would freeze its commitment or projects. Thus, for much of 2020, they adapted their focus concerning the communities they served.

Initially, they redefined the work of Tierra Nueva under an emergency policy. During the most severe period of the pandemic, the organization focused on humanitarian assistance. Thus, they readjusted the budget to prioritize food and cleaning kits. It was difficult to donate these humanitarian packages at first because the communities were closed due to the national quarantine movement restrictions.

For the same reason, they necessarily interrupted the educational processes of the age groups. In those first months of the pandemic, the Tierra Nueva team recalled the misinformation and psychosis they observed in the communities.

However, a few months into the national quarantine, Tierra Nueva resumed educational programs and the rest of its strategic areas.

In contrast to the cities and urbanized sectors, in the rural communities, the pandemic, after the initial stir, had a lesser presence. Due to misinformation or the same isolation of the communities, movement restrictions and social distancing measures faded. People led their lives as usual, in contact and without masks.

In Tierra Nueva, they knew this rural dynamic of the communities, but that did not mean they did not make adaptations to their educational programs. On the contrary, they implemented biosecurity measures and, above all, made the programs virtual.

"The programmatic implementation stopped for about 3 months because there was no access to the communities. When the opportunity opened, the virtual training mode was implemented. An investment was made in basic equipment to make videos and materials. WhatsApp was used. However, there were problems. When the government launched its television program, they did not take into account that people in Huehuetenango, because of the border, watch more Mexican television. In telephony, only 30% have a smartphone."

Virtuality was not an exceptional case for Tierra Nueva, but was common in schools and educational organizations. However, in Guatemala, the infrastructure and access to technology are limited or non-existent in many parts of the country, especially in rural communities. Rather, virtuality was the educational mode that was improvised urgently, which definitely did not sustain education.

The Tierra Nueva team recognizes that distance education configured virtually scorns “the impact of human connection." Education needs interaction and socialization to remain effective as instruction and teaching. Thus, they consider that taking advantage of the normality with which they lived the pandemic in rural communities, the opportunity to gather young people in person was important not to lose entirely that human component of their programs and their alternative pedagogy.

An alternative education after the pandemic

A particularity of Tierra Nueva is its work in both urban and rural sectors. Due to this scope, they were able to observe that, unlike other case studies, the emotional impact of the pandemic-induced lockdown and distancing varied by context.

"The pandemic affected some because there was a lockdown, but in the communities, nothing much happened. They did not experience it as much as the urban area because they had more freedom. For the urban youth, the lockdown was real. In the rural area, it may have affected some, but others continued with their normal lives."

The sometimes indifferent normality of the rural communities against the pandemic psychosis of the cities was a particular phenomenon witnessed by Tierra Nueva. Hence, the push for specific psychological processes or programs for the pandemic was not a priority or necessary. Instead, Tierra Nueva focused more on other areas: food security, migration, and youth training.

With regard to the latter, the link with Glasswing was crucial. For the adolescent age group, with the established development centers and the lessons learned from the virtual mode, they implemented two educational programs with Glasswing. First, they virtually redesigned English courses that had never been integrated into the curriculum of Tierra Nueva.

Second, they launched the project “Young Leaders for Central America." The purpose of this program is to root the youth to their territories in the face of migration desires, create community identity and projection, and professionally train young people in their search for work or entrepreneurship projects.

"We serve young people both in and out of the system. They receive a training process so that they feel identified with their community, know the traditions, people. In the first phase of a month, they must present an audiovisual material. The second phase lasts 6 months, where they receive training workshops, tutoring, mentorships, events. Additionally, they undertake a practice or community service. There is also a financial training process to manage economic resources. In the third phase, the youth can outline a community project. As a group, they identify a problem and make a proposal, defend it with Glasswing, and are provided resources. They have a platform where they accumulate points to win prizes and interact with various youths in different municipalities. In the third phase, there is also an opportunity for those not actively employed to link up with a private company where they would do their work practice."

The horizon of Tierra Nueva

Not even a global pandemic was enough to completely interrupt the trajectory and work of Tierra Nueva. However, it did mean that the team had to readapt and redefine the methodologies, programs, and focuses of the organization. They also faced budget difficulties due to the reduction in investment as well as having to train out of necessity, against the clock, and however possible.

Despite everything, they remain standing; the work has not stopped. Before the new and unpredictable problems left in the wake of the pandemic, as summarized by the director of Tierra Nueva, “there is no slope that does not cost, but there is no slope that does not end; at the top, there is another much broader horizon.”

In that broad horizon lies the desire to strengthen and grow institutionally. Indeed, they call it “the institutional development model.” The essence of this new model for Tierra Nueva rests on the official certification of all programs.

"At this moment, the step we would like to take is for the Ministry of Education to certify our processes. Thus, an infant spends five years in the stimulation centers, finishes the program, and moves on to the next age program. They receive a certificate from us, but it would be great if the Ministry issued a certificate stating that for five years, they have received stimulation, as well as in literacy. For the past five years, we've been thinking about whether to become an educational institution or not."

They consider it would be beneficial for Tierra Nueva if they could achieve a relationship like the alliance with DIGEEX. Through DIGEEX, they certify the young participants. However, the rest of Tierra Nueva's work is not officially recognized in any way.

Overall, it would be fundamental if they could realize the institutional development model. Indeed, the team of Tierra Nueva reiterates that they have “a very strong institutional wealth.” They have developed materials, educational modules, training programs, diplomas for teachers, development centers, an alternative pedagogy. In short, they have a solid and experienced base.

Tierra Nueva has always dreamed big. Alongside their dreams has remained, unwavering, the commitment to transform the drastic reality of the communities through trained youth. At Tierra Nueva, they see that on the horizon lies education.

Notes

General notes

This product was designed, visualized and written by the Population Council Guatemala team, with collaboration and feedback from the Tierra Nueva NGO team, for the project Recovering Education in Central America: Activating Networks and Associated Groups (RECARGA).

The images presented were taken from the social networks of Tierra Nueva NGO, shared by its team or photographed by the Population Council Guatemala team. In external cases, the source was indicated.

Specific notes

1. The department is home to several pre-Columbian centers, which demonstrate the occupation of the territory since the preclassic period (there is also a paleontological site, which shows the presence of hunter-gatherer groups).

2. Thanks to the topography and remoteness of Huehuetenango, the indigenous peoples were sufficiently isolated. Therefore, they had relative autonomy in their cultural development, which differed from other indigenous peoples in other areas of the country.

3. They decided on the NGO figure because it adapted to the original intentions of receiving funds, employing local professionals and developing important projects.

4. On February 15, 2024, the Population Council team held a participatory workshop, lasting six hours, at the Tierra Nueva facilities. 12 people from the Tierra Nueva team participated.

The objectives of the workshop were, through a guided group discussion and timeline, a) collect the local history of Huehuetenango, b) document the organizational and educational development of Tierra Nueva, especially during and after the pandemic, and c) understand the educational ecosystem in which the partner is located.

One of the products was this case study in the form of a narrative history, prepared after a process of systematization of the workshop, bibliographic review, statistics, audiovisual archive and interview. The shorthand was a collaboration between Population Council and Tierra Nueva NGO.

Bibliography

Banco Mundial. (2013). Guatemala: En 44% de los municipios rurales, tres de cada cuatro personas viven en pobreza. World Bank. https://www.bancomundial.org/es/news/press-release/2013/04/30/mapa-de-pobreza

Castillo, M. (2019, diciembre 23). Cuántos niños dejan la escuela a diario en Huehuetenango por pobreza o por la necesidad de migrar. Prensa Libre. https://www.prensalibre.com/ciudades/huehuetenango/cuantos-ninos-dejan-la-escuela-a-diario-en-huehuetenango-por-pobreza-o-por-la-necesidad-de-migrar/

Garay Herrera, A. J. (2014). Las lecturas múltiples de una frontera: Huehuetenango y la Sierra de los Cuchumatanes. Boletín Americanista, 69, 79–96.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística Guatemala. (2018). XII Censo Nacional de Población y VII de Vivienda.

Maldonado Valle, C. (2022, enero 5). Huehuetenango, Totonicapán y Alta Verapaz son los peores departamentos para la niñez. Ojoconmipisto.com. https://www.ojoconmipisto.com/huehuetenango-totonicapan-y-alta-verapaz-son-los-peores-departamentos-para-la-ninez/

McCreery, D. (1989). Tierra, mano de obra y violencia en el altiplano Guatemalteco: San Juan IXCOY. Revista de Historia, 19, Article 19.

Pérez, A. (2014). La chispa que encendió la conflictividad en San Mateo Ixtatán. Plaza Pública. https://www.plazapublica.com.gt/content/la-chispa-que-encendio-la-conflictividad-en-san-mateo-ixtatan

Selee, A., Argueta, L., & Hurtado Paz y Paz, J. J. (2022). Migración de Huehuetenango en el Altiplano Occidental de Guatemala. Respuestas de políticas públicas y desarrollo. Migration Policy Institute y Asociación Pop No’j. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/mpi-huehuetenango-report-esp_final.pdf

Tejada Bouscayrol, M. (2010). Historia social del norte de Huehuetenango (2a ed.). Centro de Estudios y Documentación de la Frontera Occidental de Guatemala (CEDFOG).

Torres, S. (s/f). Proceso social de lucha en Guatemala: El caso del norte de Huehuetenango frente a la violencia de Estado (1960-2016). http://conti.derhuman.jus.gov.ar/2018/03/seminario/mesa_36/torres_mesa_36.pdf