Case Study: La Esperanza

Hope before La Esperanza

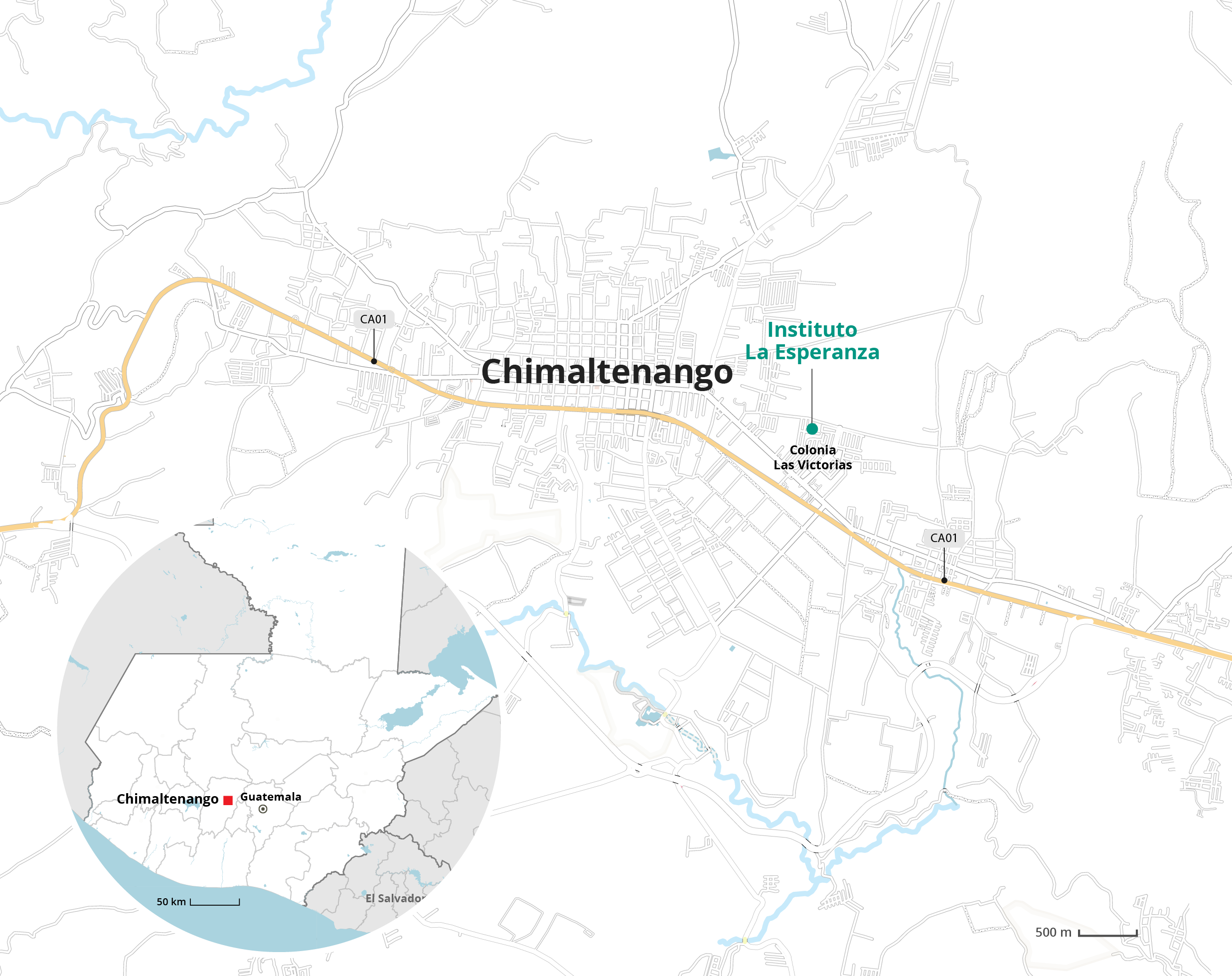

In the heart of Chimaltenango, in Zone 6, lies the Las Victorias neighborhood1. Navigating its streets, one encounters gates and fences that transform the area into an urban labyrinth. Deep within the neighborhood stands a building distinguished by a vibrant mural, symbolizing hope growing through the cracks of the asphalt: the educational institute La Esperanza.

Mothers and teachers at La Esperanza recall the days of violence that plagued Las Victorias between 2005 and 2010. Known officially as a “red zone,” it was an area fraught with danger.

Gangs of youths who owned little more than the streets were a common sight. Their lives were marked by domestic violence, poverty, and despair, with gangs and vandalism often serving as their limited or sole alternatives.

Going to work or stepping out at night was risky because of muggings. No vendors would enter the neighborhood, and bus drivers avoided it because it was considered a hotspot for crime. Murders were frequent throughout the area

This youth was entirely neglected by the state and the educational system.

At that time, an NGO called Popol Wuj provided education at a very low cost and was highly valued by the community for offering quality education. However, it closed due to funding issues, forcing many students to enroll in public schools.

Despite free education policies under President Álvaro Colom (2008-2012), public schools were either overwhelmed by demand or rejected students due to their age.

In this context of poverty and violence, with many young people excluded from the educational system, three women combined their knowledge, experiences, and hopes to address the social needs of at-risk2, impoverished youth in Las Victorias.

One of them, who would later become the director of La Esperanza, worked from 2008 to 2012 at CONALFA on a literacy project for adult and indigenous women, teaching reading courses and a fast-track primary program to illiterate women from Las Victorias.

"In 2011, I did my EPS3 (social service) at the USAC in pedagogy and educational administration. I took that opportunity to propose an educational center for the community’s underprivileged students. This arose because I was teaching literacy to the women in the community... and once, the women mentioned, 'the kids here have to go elsewhere for schooling after sixth grade.' I had seen many of these women’s children drop out of school for the same reason."

The director met another co-founder in 2010. She is a teacher and linguist from USAC. They used to greet each other as they passed by on the road, not yet knowing they would collaborate on a life-changing project.

Each was aware of the other's work as public school teachers and shared a common vision: an educational proposal to address the issues of violence, poverty, and youth abandonment in Chimaltenango.

Their idea was to establish a public educational center to receive state funding for staff, equipment, materials, and a building. However, when the director presented the proposal to the municipal council and then-Mayor Carlos Simaj, it was rejected. Undeterred, they transformed their project into a private civil institute.

They started with a few teachers and constructed a simple metal-sheet structure while awaiting official accreditation from the Ministry of Education.

The local educational supervisor, familiar with the sector’s challenges and supportive of educational projects, promised to expedite the official student registration process.

By the end of March 2012, as if destined to survive against the odds, La Esperanza was born.

Urban context of the City of Chimaltenango

Chimaltenango was officially declared a city in 1926, but it was not until the end of the 20th century that urbanization intensified, transforming it into a commercially productive and geopolitically dynamic city.

According to SEGEPLAN —General Secretariat of Planning and Programming of the Presidency—, for 2018 Chimaltenango had the highest degree of population density per square kilometer and constant population growth.

According to SEGEPLAN —General Secretariat of Planning and Programming of the Presidency—, for 2018 Chimaltenango had the highest degree of population density per square kilometer and constant population growth.

According to the 2018 national census by INE, the entire population of the municipality resides in an urban area. However, the city lacks order and distribution, a product of urban improvisation due to state planning failures and unregulated private interests, resulting in inequality.

Not all areas of the city have access to basic services such as water and electricity. The demographic growth, driven by both long-term residents and permanent or temporary immigrants, has overwhelmed the city, pressing for resources and space that, without state planning or regulation, are insufficient or inefficiently distributed.

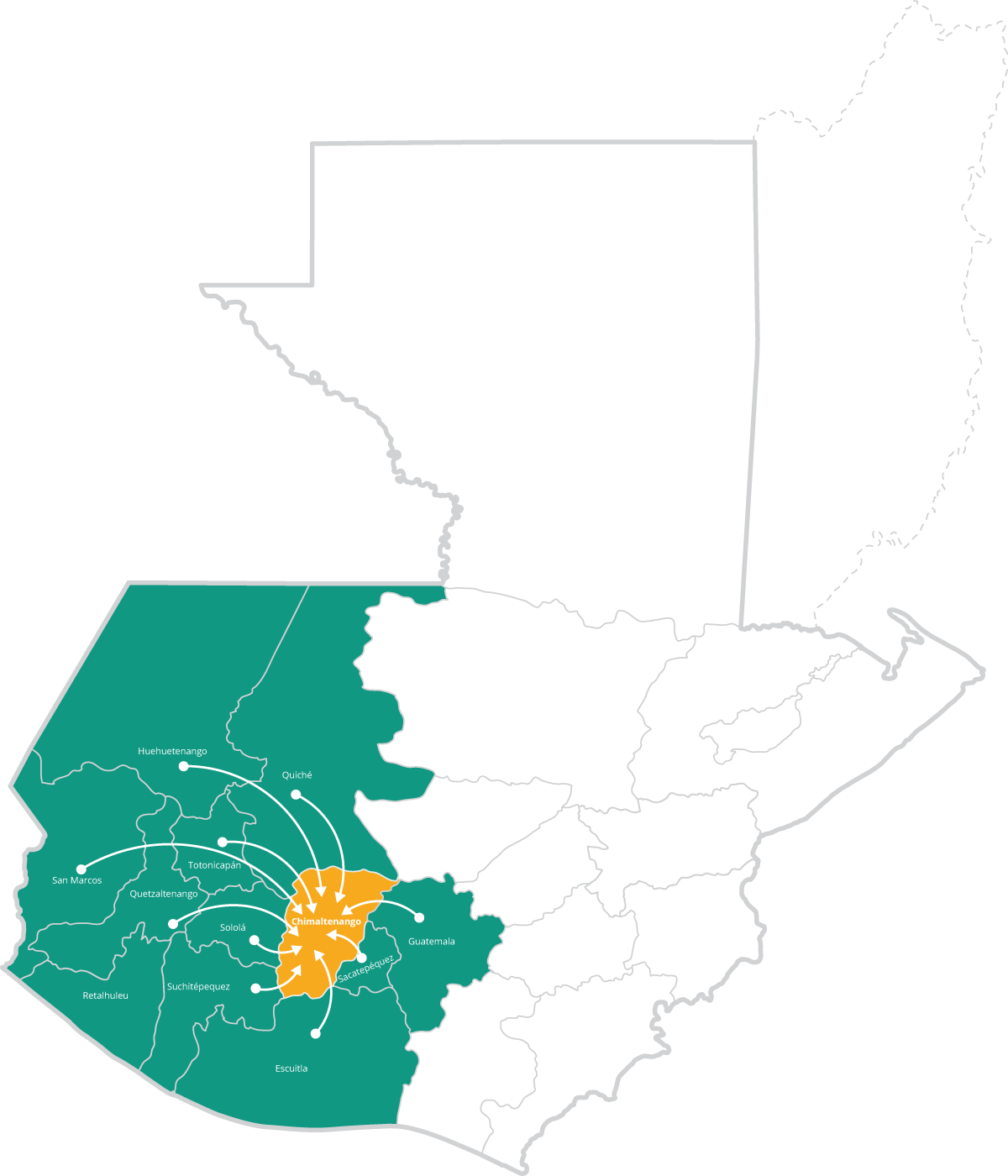

According to SEGEPLAN, migration to Chimaltenango has proliferated in recent years. They come from departments such as Quiché, Totonicapán, Sololá, Quetzaltenango, Huehuetenango, San Marcos, Sacatepéquez, Escuintla, Mazatenango, Guatemala and other places for commercial reasons.

According to SEGEPLAN, migration to Chimaltenango has proliferated in recent years. They come from departments such as Quiché, Totonicapán, Sololá, Quetzaltenango, Huehuetenango, San Marcos, Sacatepéquez, Escuintla, Mazatenango, Guatemala and other places for commercial reasons.

Another tragic consequence of the unequal city is urban violence. A city that fails to fulfill its citizens' fundamental rights, with neglected and forgotten outskirts, provides fertile ground for gangs and criminal activities.

Youth are at the center of this urban violence. While they are often the perpetrators, they are not the primary culprits. Beyond being violent, the youth are victims of violence, especially state violence they face daily.

Gangs are primarily youthful groups. However, youth are not inherently violent; they are products of the need to express rebellion and seek belonging in the face of social exclusion and inequality.

The unequal urbanization is part of the state's violence, which deprives, violates, and impedes rights. The lack of attention, minimal urban planning, intentional efforts to dispossess communities and groups of territories and resources, and the reluctance to accept accountability are forms of state violence.

Youths and gangs are not just objects of the urban violence prevalent in cities like Chimaltenango; they are also victims of state violence that deprives them of fundamental rights: education, health, housing, recreation, security, and the integrity of their lives.

Popular education at La Esperanza

The first group enrolled at La Esperanza consisted of 28 students, young people who had grown up on the streets, speaking the language of urban violence.

"These kids were street kids, some were involved in criminal activities. We had people in the neighborhood who were involved in serious matters. The youths had strong personalities and expressed themselves however they wanted."

Due to this student profile, prejudiced neighbors in the colony labeled the institute as “preventive.” Despite these stigmas, La Esperanza refused to deny these youths enrollment because they were precisely the population that needed the most attention.

It was an example of intentional recruitment. It was a significant practice for La Esperanza because it reached the most vulnerable population of Las Victorias.

Initially, teaching the first group was challenging as it became a “power struggle” between the rebellious streetwise student and the traditionally educated public school teacher.

"Young people with many behavioral problems, low self-esteem, and adaptation issues. Sometimes classes couldn't be held because it was just chaos. The kids were undisciplined. Moreover, there were various educational levels. It was quite complex."

However, the founders of La Esperanza were clear about whom they were dealing with and the reality of Las Victorias. They knew it was a context of urban violence and poverty, with young people whose rights were systematically violated, and especially youths whose rebellion and indiscipline were symptoms of something deeper: proactivity.

This understanding led to the creation of one of their first essential programs: the leaders' club. Initially, it consisted of a series of excursions and workshops aimed at activating the youths, recreating the students, and providing reflections on their realities and biographies to transform them into leaders of their lives and communities.

"These kids were leaders because they had a lot of energy and potential, but it was misdirected. 'We are going to make good leaders out of them,' so we started working with art, theater, leadership, and active school methods."

As they progressed, the educational and rebellious disconnection of the students, fueled by a street life prone to delinquency and violence, led them to conclude that teaching needed an approach that suited the needs and personalities of the youths.

They then took on the task of studying books about Paulo Freire's popular education4 due to its horizontal philosophy with the student. Guided by this, in 2012, through a Facebook ad, the director enrolled in a workshop that aligned with La Esperanza's vision: the Alternatives to Violence Program (AVP).

A pedagogy against Violence

The director attended the three-day workshop, conducted by women from California, USA. The AVP is an educational conversion of a social approach initially used by Quakers in the United States to counteract the deadly violence occurring within prisons.

At the workshop, the director saw the AVP as a form of popular education.

She then requested the workshop facilitators to conduct the AVP at La Esperanza, which they agreed to without delay. This marked a foundational pillar for the institute.

The AVP is held at La Esperanza for two days in March and again in June each year. The facilitators of the workshop are participants from previous workshops who have been certified after three levels of training. They are responsible for guiding the workshop through playful activities and reflection.

According to teachers and students at La Esperanza, the AVP is both a transformative experience pedagogically and personally; it involves “unlearning to learn again.” That is, it deconstructs the internalized ideas, mandates, and methods of traditional education. It involves relearning, indeed, in a shared space and process among teachers and students.

"One of the kids who was most involved in crime and convinced that was his path, cried during the workshop, explaining why he did things, why he stole snacks from classmates, why he harassed the girls... He was the first to click and became a leader in the leadership group. Later, he became a facilitator for the workshop, helping other children and young people."

The AVP transforms participants because it is based on the critical reflection of personal and educational aspects. That is, to listen is to contextualize.

Overall, the AVP at La Esperanza represents a pedagogical break from traditional education. It is also a rite of passage for new teachers and students; that is, a transition from an often exclusionary and rigid education to an education that dialogues, listens, plays, and critiques. Some are so ingrained in the traditional method that they resign from the popular education at La Esperanza.

Growing inward and outward

The period from 2012 to 2019 was a time of consolidation and projection for La Esperanza.

Initially, the student body grew from 28 to 47 students, key programs and methodologies like the leaders' club and the AVP were established, and new teachers joined. At the same time, educational and institutional challenges emerged.

Firstly, integrating popular education into the official curriculum was challenging. La Esperanza has always been envisioned as an educational center that would cover young people excluded from public and private education, as well as accredit them in the educational system to give them an official place in the labor market or university.

They are required to meet the official requirements of the Ministry of Education (MINEDUC). That is, teaching certain topics, a quota of grades, instruction for minimum competencies.

To address this, they devised a mixed curriculum that includes official content from the educational system and programs from popular education. Thus, they meet the requirements of MINEDUC without losing the pedagogical essence of La Esperanza.

On the other hand, funding the institution is another challenge. The director is responsible for sending proposals and presentations to various financing competitions and international donors.

Therefore, the institute is sustainable due to the financing from international organizations that believe in their work and have seen results. Since 2016, they have covered administrative, salary, and material costs. Additionally, they have been able to fully scholarship5 all the students.

It has also been essential for retaining teachers who, under other circumstances, would have been forced to seek income elsewhere.

Educational and institutional partnerships

The new contents and programs that La Esperanza gradually explored or acquired necessitated coordination and relationships with other organizations. Thus, partnerships became essential. In the case of La Esperanza, these began from the inception of the institution.

La Esperanza in pandemic times

In March 2020, the government of Alejandro Giammattei decreed a national quarantine due to the outbreak of COVID-19. The population retreated to their homes, leaving the streets of the cities empty. It was a time when the chirping of birds could be heard over the honking of cars, and regular pedestrians were replaced by wild animals.

With businesses improvising remote work arrangements, computers and cell phones became not only the main tools for work but also the only links to the outside world. However, this was only the case for those who could afford a device and internet service.

The pandemic reminded us in Guatemala that technology is a privilege.

In education, given the official measures for social distancing and public hygiene, schools, and colleges closed their facilities and were forced to adapt to distance learning methodologies.

However, technology was far from a panacea for education, considering its limited context and access in Guatemala.

Various methods were devised to address the education of millions of children and young people: text messaging or WhatsApp, phone calls, rounds of home visits to drop off worksheets or pamphlets, and audiovisual courses produced by the Ministry of Education for television and radio.

Education was unprepared for the tragic scope that the pandemic would bring, exacerbating the structural and historical deficiencies of the public and private educational system. Notably, the closure of schools and colleges lasted until 2022.

This resulted in the closure of private educational centers, impoverishment of household economies, inefficient pedagogies due to limited access to the internet and technological tools, and especially a lag in learning.

Everyone rise up

But how did La Esperanza experience the pandemic times?

Physical presence is a fundamental aspect of popular education, as there is a component of the body through physical activity, play, interaction with the group, the space, and the teacher. Therefore, at La Esperanza, they could not overlook face-to-face classes.

Given the difficulty and complexity of fully implementing remote classes, they opted to call students to the La Esperanza facility on some days. They called this reinforcement. Students who needed help or review for certain subjects attended voluntarily.

While they took public health measures against COVID-19 very seriously, they had discussions with the educational supervisor from MINEDUC.

"She came with the mentality of wanting to close us down during the pandemic, even though we were providing tablets to the kids for them to receive classes. She wanted to close us because they said we were holding face-to-face classes. We explained that it was due to the needs of the kids."

The outcome of the dialogue was to respect MINEDUC's dispositions by agreeing with the supervisor that a limited number of students could gather.

On the other hand, La Esperanza's teachers took on the responsibility of calling or personally messaging parents to ensure no student was left without attention or follow-up.

Despite all these pedagogical efforts, early signs of the pandemic's legacy began to show at La Esperanza. Student dropouts, learning problems, and young people who were disheartened and anxious were evidence of the pandemic's impact on the youth.

It was after the lifting of social distancing and public hygiene measures in 2022 and 2023 that they faced an adverse reality.

The emotional and social ravages of the pandemic

When classes resumed, few students wore masks. They were hiding not just their faces behind them, but also their hearts. The impact of the pandemic extends even into the most precise corners of our societies: the emotions.

"Young people came with a lack of interest in learning and doing anything. We saw it more in the young people who did not show up [for reinforcement]. Young people don't talk, don't communicate. Communication was lost. Emotionally, self-esteem was low. Even at times when there was no need to use a mask, there are young people who, during lunch, would put their food into the mask. They said, 'I'm ugly,' even eating embarrassed them. There was a lot of anxiety; many kids were depressed."

The pandemic emotionally devastated many young people, boys, and girls. At such a young age, confinement meant being physically separated from the world, from the community, from their peers. Without socialization or stimulation, they were relegated to the little or nothing socially offered by the home. Additionally, many homes had tragic stories of death from COVID-19, which represented additional traumas.

Moreover, the cell phone, the only access and link to their community and peers, influenced them. At La Esperanza, it is asserted that the cell phone made young people anxious as it became a crucial extension of their lives. It turned into “an addiction” and “a dependency.”

If the cell phone was the only social access and link for young people, boys, and girls, the loss of communication and participation in the face-to-face classes at La Esperanza is understandable. Interacting with the cell phone is done behind the screen as a social spectator. In contrast, due to the circumstances of the pandemic, the young people did not learn how to interact with their peers and their teachers. They were not social actors.

Students were not the only ones emotionally torn apart by the pandemic. Teachers were as well.

"We are used to working face-to-face. I had a stress breakdown because the burden was triple. It was so much because it wasn't just being a teacher but also being a mother. I got quite seriously ill. I have a daughter who is a nurse, and she took care of me. One does not realize one is sick because, as I love what I do, I lose myself in work and didn't listen to my body."

When she refers to a triple burden, she identifies the labor burden of education, the domestic life of the home, and the pressure of the educational system that falls on the teacher. Now, in a context where education has been and continues to be disarticulated by the State, the teacher often finds herself alone, occasionally with only the company of other teachers like her, carrying the abundant responsibility and mission of attending to education.

The concern for knowing the fate of the students, the anxiety to ensure good education, the stress of family life, and the abandonment by public authorities, all in a context of risk and panic due to COVID-19, easily fracture the mental and physical health of the teaching profession.

No one left behind

Faced with this pandemic reality that wreaked havoc on students and teachers, La Esperanza did not remain idle.

Therapy spaces worked by psychologists have been common given the emotional afflictions of the students during the pandemic. Additionally, teachers described that most students came with a lot of energy accumulated over the lockdown. As one parent described, “they seemed like little goats just let out of the pen.”

On the other hand, they encountered groups of students with learning deficiencies. Every year they conduct “diagnostic tests”6 in order to know, although they are not limited to them, the learning level of students in certain subjects.

In 2023, the results of the diagnostic tests in math and reading for all secondary and diversified grades were not encouraging. Among the groups, they encountered serious learning differences between new students, or students who did not attend the reinforcement, and students who received educational reinforcement from La Esperanza.

"There was a marked difference between those who came to reinforcement and the rest of the students. At the beginning [of returning to classes], an evaluation was done. The figures and statistics mark the difference. The youths from the reinforcement read 268 words, and the others 100. The teacher divided the class into three groups for math because the kids wouldn't understand. Similarly, reading was organized: not by grade but by levels of learning. Level one struggles to read; two is a level of comprehension; and three to the logical."

Many of the students coming from public schools were the ones with the worst diagnosis. For this reason, at La Esperanza, they resorted to dividing groups by levels of learning, tutoring, and personalized reinforcement.

Especially reading is an area of learning that they consider fundamental and where they have directed most priority and urgency. They believe that a student with reading skills can “learn anything.” Reading is the basic gateway to knowledge.

They have also witnessed deficiencies in technological skills among many students. Thus, they encountered students who could not turn on a computer, who struggled to use a mouse, and who found it difficult to use a cell phone for tasks.

Despite the existence of cell phone dependence, this does not imply its conscious or productive use. As one of the teachers described, “the cell phone is not synonymous with technology.”

Therefore, since 2020, in search of better technological tools, partly forced by distance classes, they have committed to technological education.

For this, they partnered with an Israeli company that offers technology to young people who have never had access, with TechnoKids Guatemala and Tecnikids. Therefore, they now work on online STEM education with programming and robotics courses.

Despite all these efforts and projects to attend to the youths who were left behind emotionally and educationally, they would not have been possible if the teaching staff did not have a clear vision of La Esperanza, which gained more strength and urgency during the pandemic.

La Esperanza adopted a quote from the Popol Vuh to make it their motto and slogan that summarizes their vision: “Let everyone rise up; let no one be left behind.”

Artistic Festival - Commemoration of International Youth Day

Artistic Festival - Commemoration of International Youth Day

Robotics for children

Robotics for children

Artistic expresion area

Artistic expresion area

Harvest of the first fruits in the space that they dream of turning into an ecological school.

Harvest of the first fruits in the space that they dream of turning into an ecological school.

The legacy of La Esperanza

Since its founding in 2012, the history of Las Victorias has been linked to the history and project of La Esperanza. They believe that the social and educational work of the institute and the teaching with the youth forgotten by the state and the city of Chimalteca has borne fruit.

Gone are the days of violence and delinquency from 2005-2010. A sign of this is the current profile of the students. From youths at risk or involved in criminal activities, they are now, as one teacher mentioned, “more innocent children” or relatives of students who graduated from La Esperanza.

The path forward

In 2021, they acquired a plot of land in Chimaltenango. Unlike the current location of La Esperanza, it is not central. With the help of student volunteers from the leaders' club, they dedicated themselves to cleaning the place. Currently, they use the land for entrepreneurship activities, leadership, sports, or band rehearsal.

From these ideas to expand La Esperanza to other territories of Chimaltenango, they may encounter an inescapable reality of the department: the Mayan presence.

Chimaltenango has a significant Mayan population, especially a rich history of Kaqchikel groups dating back to pre-Hispanic times.

Despite the history and Mayan presence, Guatemalan cities specialize in erasing or ignoring ethnic identities.

In the case of La Esperanza, they do not avoid this reality. They have worked with Mayan youths in addition to offering Mayan language courses in their curriculum. However, intercultural education is not one of their main focuses of popular education.

But they have reflected on the projection of La Esperanza beyond Las Victorias. For example, they mentioned that they have no relationship with the most historically significant school in Chimaltenango: the Pedro Molina.

Therefore, they are at a moment where they feel prepared to expand their horizon. Not only to establish themselves in other territories but also to share the testimony of Las Victorias, the popular education of La Esperanza, with other institutes, schools, or colleges.

They know there are more young people at risk from urban violence who cannot afford their education. They live in an unequal city. Therefore, they are clear that the path forward is precisely hope.

Notes

General notes

This product was designed, visualized and written by the Population Council Guatemala team, with collaboration and feedback from the La Esperanza team, for the project Recovering Education in Central America: Activating Networks and Associated Groups (RECARGA).

The images presented were taken from La Esperanza's social networks, shared by its team or photographed by the Population Council Guatemala team. In external cases, the source was indicated.

Specific notes

1. On September 22, 2023, the Population Council team held a participatory workshop, lasting six hours, in La Esperanza. Nine people participated:

► Seven from La Esperanza. The two co-founders, one of them a director and the other a teacher; the person in charge of administration; four teachers of different subjects.

► Two mothers of the family. One of them leads the values group of the local church. The other mother has a history of family members enrolled in La Esperanza for many years.

The objectives of the workshop were, through a guided group discussion and a timeline, a) to collect the local history of Las Victorias, b) to document the organizational and educational development of La Esperanza, especially during and after the pandemic and c) understand the educational ecosystem in which the institute is located.

One of the products was this case study in the form of a narrative story, prepared after a systematization process of the workshop, bibliographic review, statistics, audiovisual archive and interviews.

2. In La Esperanza they understand youth at risk as, first, the possibility that young people are attracted to the culture of urban violence (gangs, delinquency, organized crime) and, second, that they are victims of said violence.

3. The EPS is a practical, preparatory evaluation of the USAC. It is a requirement to complete the degree.

4. Popular education calls into question the traditional pedagogy that has rejected and excluded these young people: a behaviourist, punitive, vertical, productivist one. It is a horizontal and bidirectional education, teacher-student and vice versa. It does not have an authoritarian sense when imposing knowledge or mandates, but rather it interacts and dialogues with the student, guiding them to critical thinking. Its pedagogical purpose is to train in and for freedom, so it is necessary to educate the student and the teacher comprehensively.

5. La Esperanza's only criterion for a scholarship is if the student shows dedication and perseverance in studying. For La Esperanza, the grades demonstrate little of the spirit, the educational will. Hence, in high school there is no repetition.

6. Learning diagnoses have been present since the beginning of La Esperanza. In 2015, for example, the organization participated in a study by the Educational Research Center of the Universidad del Valle de Guatemala. The third grade level was evaluated in mathematics and reading subjects, and the results were compared in relation to three other educational establishments.

Bibliography

Ajxup, V., Rogers, O., & Hurtado, J. J. (2010). El Movimiento Maya al fin del Oxlajuj B’aqtun: Retos y desafíos. En El movimiento maya en la década después de la paz (1997—2007) (Primera edición). F&G Editores.

Banco Mundial-UNICEF-UNESCO. (2022). Dos años después. Salvando una generación. The World Bank Group. https://www.unicef.org/lac/media/35631/file/Dos-anos-despues-salvando-a-una-generacion.pdf

Consejo Departamental de Desarrollo de Chimaltenango. (2010). Plan de Desarrollo Departamental de Chimaltenango. https://portal.segeplan.gob.gt/segeplan/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/400_PDD_CHIMALTENANGO.pdf

Cumes Simón, A. E. (2004). Interculturalidad y racismo: El caso de la Escuela Pedro Molina, en Chimaltenango, Guatemala [Tesis de maestría, Guatemala: FLACSO, Sede Guatemala]. http://repositorio.flacsoandes.edu.ec/handle/10469/1844

Del Águila, J. P. (2020). Prevenir la violencia: El reto de tres municipalidades en Chimaltenango. Ojoconmipisto.com. https://www.ojoconmipisto.com/prevenir-la-violencia-el-reto-de-tres-municipalidades-en-chimaltenango/

Esquit, E. (2007). Debates en torno a la identidad y el cambio social en Comalapa, una localidad del altiplano guatemalteco. En Mayanización y vida cotidiana. La ideología multicultural en la sociedad guatemalteca (Vol. 2). FLACSO CIRMA Cholsajam.

Fernandez Cervantes, J. M. (2017). Chimaltenango: La suma de todos los males en una carretera. Plaza Pública. https://www.plazapublica.com.gt/content/chimaltenango-la-suma-de-todos-los-males-en-una-carretera

Freire, P. (2007). Pedagogía del oprimido. Siglo XXI Ediciones.

Freire, P y A. Nogueira. (2007). Qué hacer: teoría y práctica en educación popular.

Gobierno Municipal Chimaltenango & Secretaría de Planificación y de Programación de la Presidencia. (2018). PDM - OT Plan de Desarrollo Municipal con enfoque en Ordenamiento Territorial.

Gómez Damman, R. (2018). Guatemala: Causas y efectos de la incorporación de niños, niñas y/o adolescentes al crimen organizado y pandillas juveniles en el departamento de Chimaltenango (enero de 2012 a junio de 2017). Una propuesta de política pública preventiva. [Tesis doctoral]. Universidad San Carlos de Guatemala.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística Guatemala. (2018). XII Censo Nacional de Población y VII de Vivienda. https://www.censopoblacion.gt

Instituto Nacional de Estadística Guatemala. (2020). Hechos delictivos. https://www.ine.gob.gt/estadisticas/bases-de-datos/hechos-delictivos/

Marroquín, R. (2020). Chimaltenango: La sensación de que algo se hace. Plaza Pública. https://www.plazapublica.com.gt/content/chimaltenango-la-sensacion-de-algo-que-hace

Municipalidad de Chimaltenango. (s/f). Historia. Municipalidad de Chimaltenango. Recuperado el 18 de octubre de 2023, de http://www.munidechimaltenango.gob.gt/pueblo/

Oficina de Derechos Humanos del Arzobispado de Guatemala. (1998). Capítulo tercero. Los mecanismos del horror. En Guatemala Nunca Más. II Los Mecanismos del horror (1a ed., Vol. 2, p. 243). ODHAG. http://www.derechoshumanos.net/lesahumanidad/informes/guatemala/informeREMHI-Tomo2.htm

Ugalde, E. (2017). La chimaltenanguización de Guatemala. Plaza Pública. https://www.plazapublica.com.gt/content/la-chimaltenanguizacion-de-guatemala

Universidad San Carlos de Guatemala. Dirección General de Investigación. Centro de Estudios Urbanos y Regionales. (2011). Crecimiento acelerado de la población en la cabecera departamental de Chimaltenango, San Miguel El Tejar, San Andrés Itzapa y Parramos. Guatemala 2000-2010. https://digi.usac.edu.gt/bvirtual/informes/puiep/INF-2011-020.pdf