Case Study: Centro Educativo Comunitario Bilingüe Intercultural Nueva Esperanza

Waiting for peace

After 36 years of bloody war1, peace came to a broken, oppressed country. In Guatemala City, on December 29, 1996, the Peace Accords were signed, ending the conflict between the state and the guerrillas.

Peace came to Guatemala, or so was the slogan of the time. However, peace was nothing more than a symbol to aspire to, a dream to pursue. A signature, not a reality.

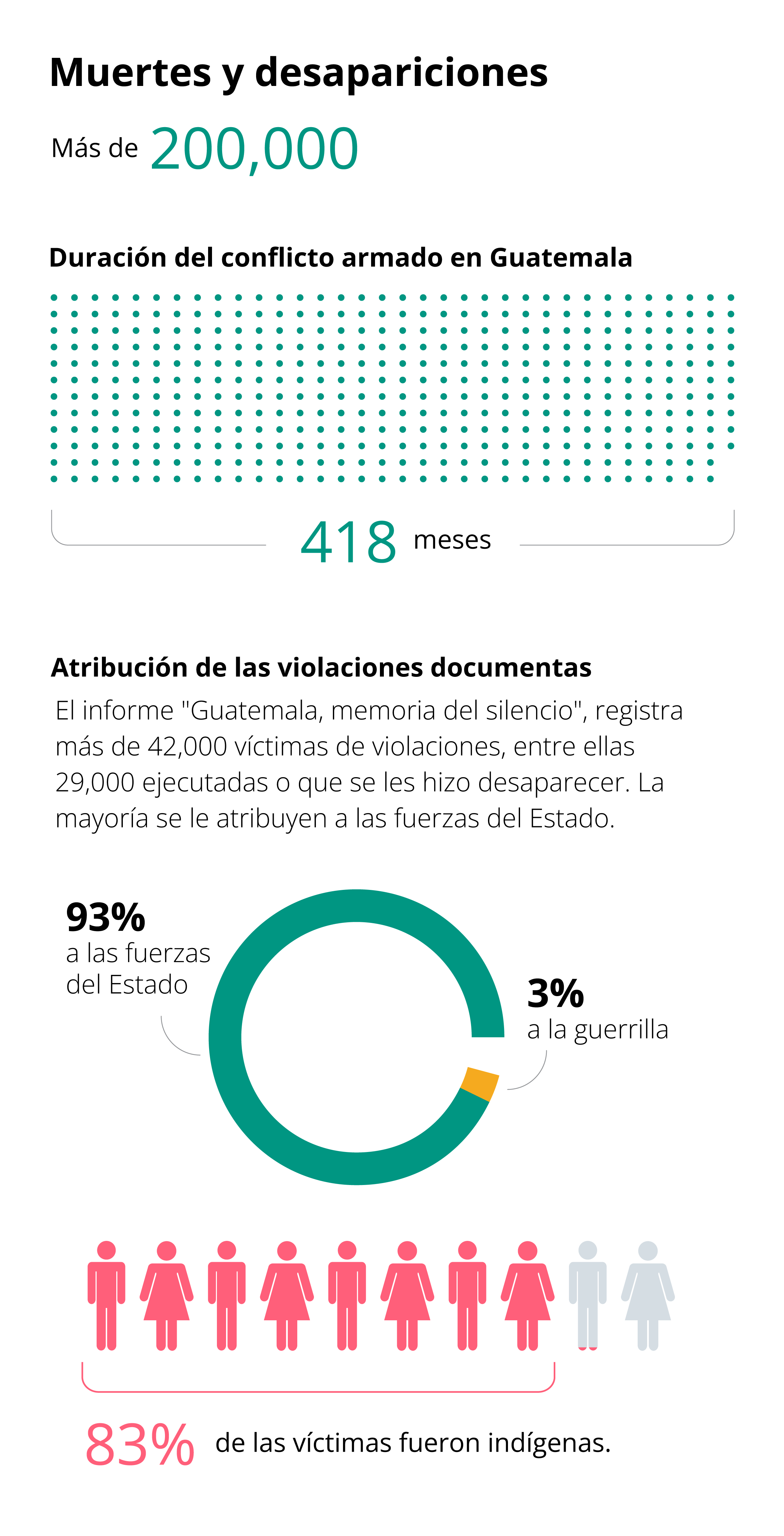

The legacy of the civil war in Guatemala has been endless assassinated leaders, innocents annihilated in crossfire, interrupted childhoods, fractured communities, and the disappeared who never reappeared or were found, much later, in mass graves. According to the Commission for Historical Clarification (CEH)2, the civil war left more than 200,000 victims, dead and/or disappeared, and over one and a half million people displaced.

A country of the dead, ghosts, and migrants.

Fuente: Comisión del Esclarecimiento Histórico (CEH)

Fuente: Comisión del Esclarecimiento Histórico (CEH)

Historically, the protagonist of violence, repression, and destruction has been the state. On the one hand, the 20th century in Guatemala was characterized by the spread and consolidation of military dictatorships.

On the other hand, the Guatemalan state has been conceived as a space for the few: the elites and the Ladinos. The independence of 1821, despite ending Spanish colonial rule, did not mean liberation for the Indigenous peoples. Indigenous peoples, who have inhabited these lands for thousands of years, have been actively and consciously excluded, dispossessed, and killed by racist states.

Thus, the state became a structure that benefited economic and political elites, and the military as a weapon against any dissident or civilian who opposed the system. For the Guatemalan state, the people were the enemy and, particularly because of its colonial roots, the Indigenous peoples.

During the civil war, the Guatemalan state had a policy of genocide against the Indigenous peoples. From the military state, there were a series of extermination and control programs directed at the Indigenous peoples: scorched earth, model communities, organization of civil militias, forced recruitment.

The achi struggle for truth and justice

In one of the many massacres of the genocide orchestrated by the state, in Xococ, native to Rabinal, a Maya Achi child survived. It was 1982, the bloodiest time of the civil war. The army and the Civil Defense Patrols (PAC) razed the village. They wanted to leave it empty, like the very souls of the soldiers. Some of the survivors were children. They were forced to live with patrol members, who settled on the ashes and blood of the devastated village. One of those children is named Jesús Tecú Osorio.

Jesús Tecú Osorio en el CECBI. Fuente: Wikipedia.

Jesús Tecú Osorio en el CECBI. Fuente: Wikipedia.

Jesús Tecú Osorio lost his parents and his brother in the Rio Negro massacres. He also witnessed the extermination of his community, his people. Thus, the experience of the war was not only an individual trauma but a community one for the Indigenous peoples.

Certainly, Jesús Tecú Osorio was a victim of the thousands and thousands of people affected by the murderous machinery of the state. However, there is no passivity in the Indigenous victims of the civil war. Framed within the Maya movement, Jesús Tecú Osorio embarked, in 1993, on a quest for truth and justice for himself, his family, and his people.

With no resources or support, threatened by the still lingering, still alive persecution of a repressive state, he approached human rights organizations, which helped him exhume the bodies of his family. Later, his determination brought to trial the patrolmen who killed his family. They were sentenced to 50 years in prison.

In pursuit of his quest for justice and his fight for human rights, on December 11, 1996, he received the Reebok Award. The same month that the country's high command signed a peace on paper, Jesús Tecú Osorio was awarded for the peace he claimed for himself, his family, and his people, and that the Guatemalan state has tried to murder.

With a considerable amount of money from the award, Jesús Tecú Osorio knew where to invest it: his community, Rabinal. His struggle was not only individual, but communal as well. It was about recovering the social, cultural fabric snatched away by the state.

A year later, in 1997, Fundación Nueva Esperanza Río Negro was born.

Historical context of Rabinal

Before delving into the history of the Fundación Nueva Esperanza, it's essential to understand the historical context of Rabinal, a territory with a long history of pre-Hispanic occupation, which still lives on in the memory and culture of today's indigenous peoples.

Pre-hispanic Rabinal and the achi people

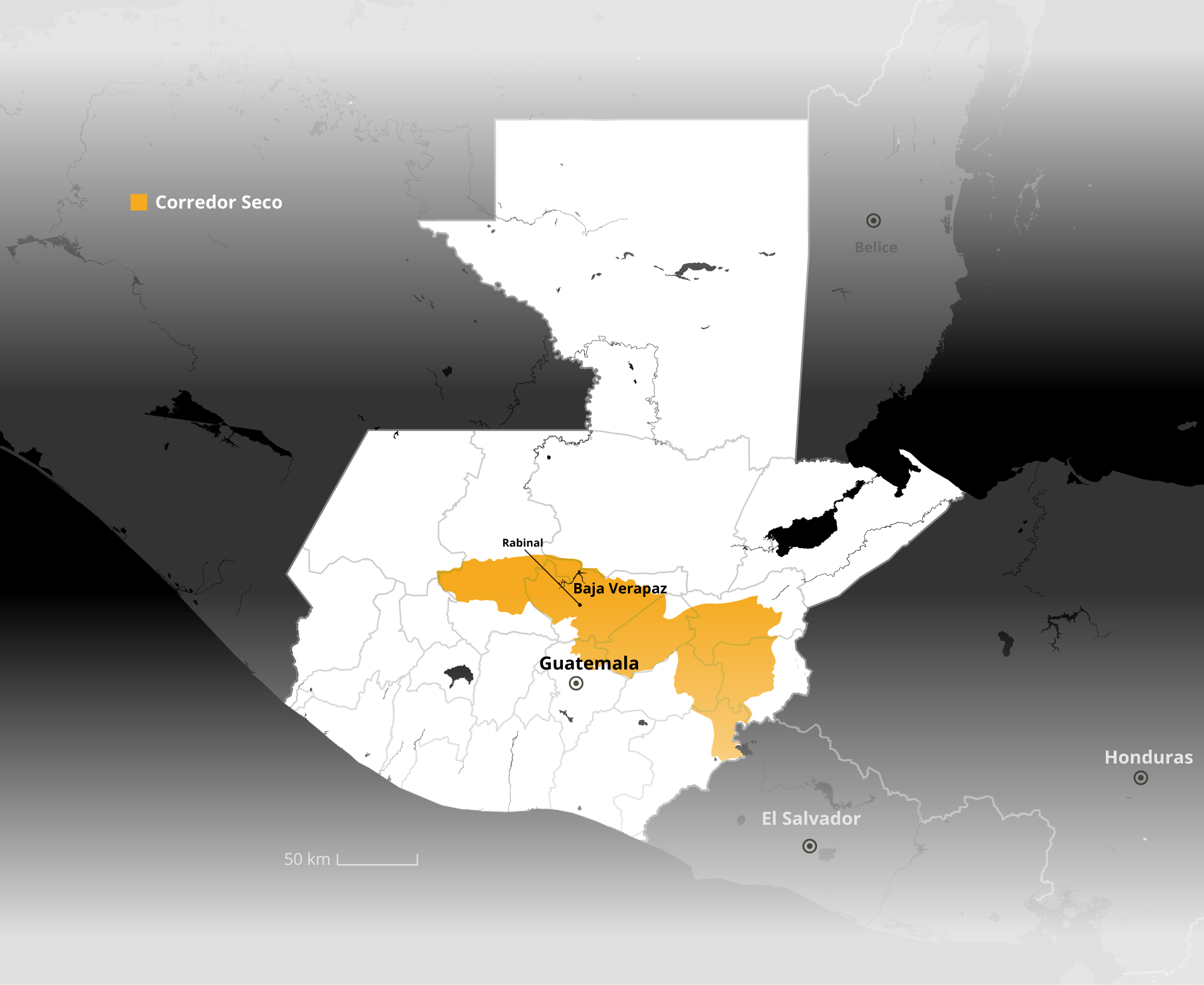

Rabinal3 is located in the central region of the Baja Verapaz department. According to ethnohistorical documentation, the territory's occupation dates back to between 800 and 300 B.C., when it was populated by Q’eqchi’ groups. Later, K’iche’ and Rabinaleb or Achi groups migrated to this region.

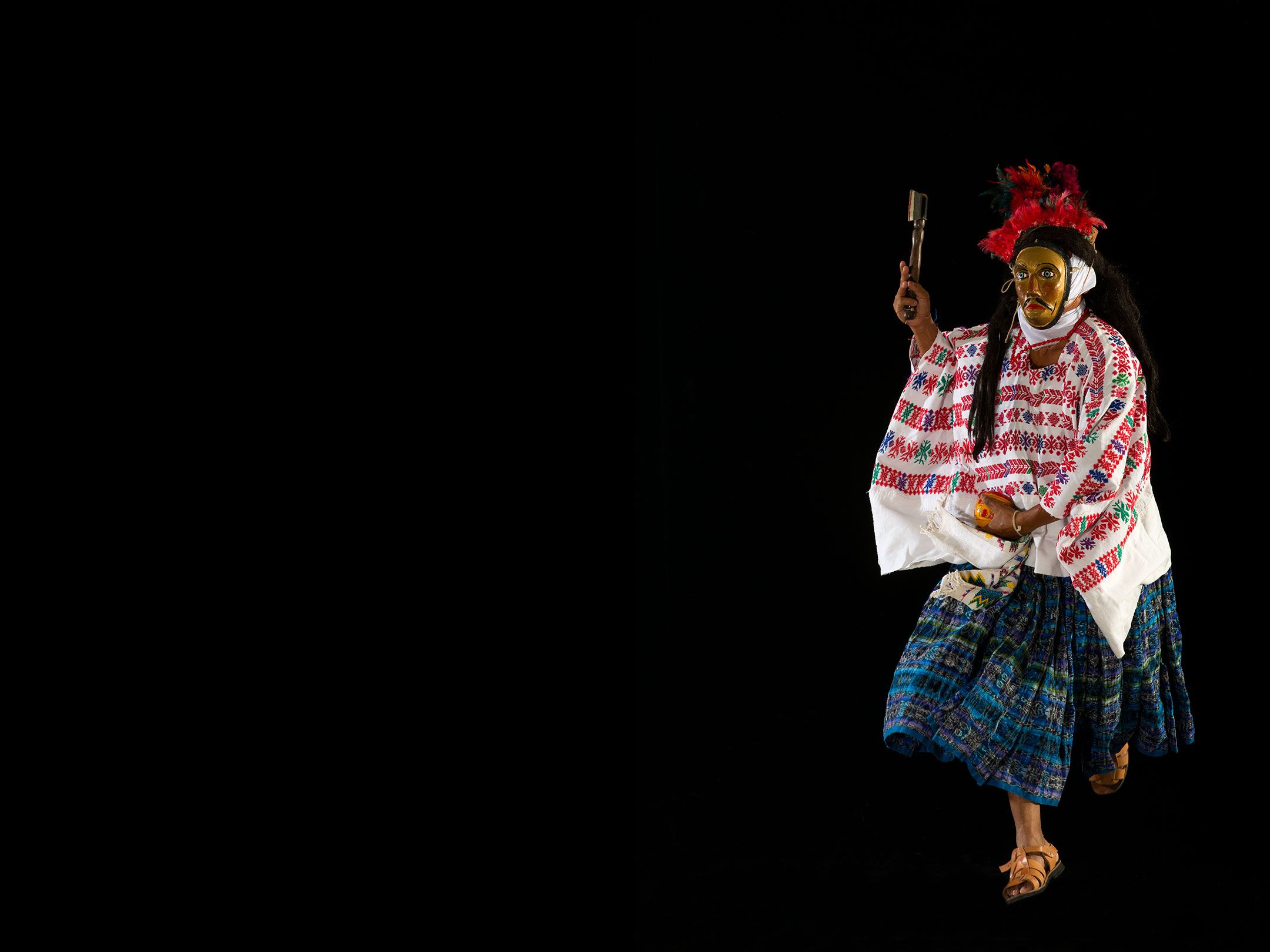

Since then, a Maya Achi population has inhabited Rabinal. One of the ethnohistorical evidence of the Achi origins is the Rabinal Achi4.

During the colonial era, at the beginning of the Spanish invasion campaign, the territory was known as "Tierra de Guerra" due to the fierce resistance of the Indigenous peoples against colonization. Faced with this opposition, Friar Bartolomé de las Casas proposed a "peaceful conquest." Colonization meant conquering through evangelization in these lands. Therefore, the colonizers named the territory Verapaz.

Shortly after the evangelization, as part of the colonial project, the reduction of peoples began. This colonial policy involved forcibly gathering colonized Indigenous populations into settlements and villages to facilitate colonial repression and control. Thus, colonial Rabinal was founded in 1538.

The civil war in Rabinal

The 20th century was a time of injustice for Rabinal. One of them stemmed from the violent collusion between extractivist development and the State. The case of the Río Negro community was exemplary of this dark alliance.

In the 1970s, the National Electrification Institute focused on the Chixoy River basin, or Río Negro, for the construction of hydroelectric plants. This project involved flooding the Middle Basin of the Chixoy River, which would lead to the disappearance of several indigenous villages, natural resources, and agricultural areas, as well as various archaeological sites. International entities such as the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank financed the dam's construction, which began in 1976.

From 1975 to 1978, the resettlement program started. Understandably, the communities rejected the project and opposed resettlement, as the State offered infertile lands with inadequate housing, and they refused to abandon their ancestral lands. True to its customary treatment of Indigenous peoples, the State neither considered nor met the communities' needs. However, the State did not limit itself to its usual neglect; instead, it initiated a series of massacres to break the resistance of Rabinal and its communities.

During those years, Guatemala was engulfed in a civil war. Under conditions of dictatorship and repression, where dissent was seen as rebellion and resulted in punishment, and a tense atmosphere within the communities due to community fragmentation, the government and paramilitary groups implemented mechanisms of terror.

In the case of the Río Negro community, between 1980 and 1982, several community leaders were killed, along with hundreds of inhabitants, including children and newborns. Entire villages were razed. In Rabinal alone, the CEH would record twenty massacres orchestrated by the State.

Rabinal in the post-war era

Part of the historical prelude to the Peace Accords was the Maya movement, which began in the 1980s. The traumas and injustices suffered by the Indigenous peoples during the civil war, along with the enormous historical debt of a state and country that had ignored their existence, fueled a massive and cultural movement that sought ethnic vindication and the demands for civil spaces and policies in favor of their rights.

The Maya movement was very present in the process of Educational Reform. Starting in 1986 during the government of Vinicio Cerezo, it was a restructuring of the national educational system. After the presence and influence of the Maya movement in the Educational Reform and the Peace process, the Agreement on Identity and Rights of Indigenous Peoples was signed in 1995.

The Agreement stipulated that the State would commit to forming educational policies based on ethnic recognition, cultural relevance, and linguistic diversity. This led to the concept of bilingual intercultural education (EBI). The EBI model seeks to meet the needs of a multi-ethnic, pluricultural, and multilingual population and state like Guatemala. It contradicts an educational system in a country where, historically, public schooling has been an institution that standardizes culture.

However, despite all the struggles and efforts of the Maya movement, there was a disappointing setback with the Peace Accords: they were not made constitutional. Therefore, the agreements remained, at best, as a framework for future policies, a social commitment, but unfortunately not enforceable5.

Rabinal in the new millennium

The historical trajectory has made Rabinal a predominantly Maya Achi municipality. They have their own language and a distinctive culture. However, despite the cultural and ethnic significance present in the municipality, it is noteworthy that Baja Verapaz is one of the poorest departments in Guatemala.

Geographically, Baja Verapaz is located in the Dry Corridor, a territorial strip guarded by the mountain range that crosses the country. Its geography is defined by aridity, leading to serious conflicts with agriculture, droughts, and food supply.

However, the main aspect of the general poverty in Baja Verapaz lies in that Rabinal and its Achi people have not only been victims of the state's historical terrorism but also the systematic denial of the most basic rights, such as education and public services, constituting an act of structural violence by the State, especially in the most remote and secluded rural communities.

On the other hand, it would be logical and appropriate for education in municipalities like Rabinal to follow the EBI model. However, the educational implementation of intercultural models is a non-existent or minimal concern in a context where public secondary education is not guaranteed.

An achi hope in intercultural education

The history of Rabinal, a relentless resistance and perseverance in the face of a violent and indifferent state, echoes another story: that of the Fundación Nueva Esperanza (FNE). It reflects the ongoing struggle of a Maya community that clings to hope against a state that did everything to strip it of a better future

As if Rabinal were a mirror in which the FNE sees its reflection, its history6 is undoubtedly an Achi struggle.

A new hope

In December 1996, Jesús Tecú Osorio returned from the United States after winning the Reebok award. This put him in the public eye and, of course, in the sight of the state.

On one side, he received threats and mistreatment from those close to the state and the military. On the other, there was the suspicion from colleagues about Jesús Tecú Osorio's new public presence, as they feared for his life. However, neither deterred him from his commitment to create the FNE.

From the beginning, the FNE aimed to fulfill a variety of missions: from vocational training to strengthening the legal system. The purpose was communal and political, as they wanted to influence community development and the vindication of political and cultural rights at the general levels of government and society.

However, it was not officially recognized, even though legal procedures had already been initiated. Its institutionalization was obstructed by the state through the Ministry of the Interior, arguing that the foundation's purposes were more appropriate to a "political party." It was not until 2003, six years later, that the FNE finally obtained legal and institutional status.

Despite the cumbersome entanglement of non-recognition, the FNE was not idle.

In 1997, they launched the foundation's first project: the artisan training center. It involved training survivors of massacres in skills such as tailoring, carpentry, and blacksmithing. The idea was to provide trades to those who had lost everything in the civil war.

From the start, the FNE considered youth education fundamental. A community devastated by war and rural poverty could not recover by neglecting the personal and academic fulfillment of its youth. Therefore, in 1998, they extended their support with a scholarship program for young people wishing to pursue secondary education.

However, after a quarter of the program, the academic performance of the scholarship recipients was unsatisfactory. They were failing subjects and falling behind in learning. They began to question whether the problem was with the program or if the youth lacked a genuine commitment to study.

They realized that the real problem lay in the educational system. The scholarship recipients were young Achi, and Spanish was not their first language. They attended a school that exclusively spoke Spanish, whose teachers were also unprepared to address the cultural and linguistic complexity of the students.

Moreover, they learned that the schools censored and ignored the teaching of the civil war, its true causes, and its grim legacy. The official school curriculum denied the historical memory of the internal armed conflict.

In the end, it was a colonial public education in the new millennium.

"How to include in the curriculum what the State does not account for: the language, the history of our people, the history of Guatemala, the internal armed conflict. Often in university, they teach you the history of World War II, while the genocide experienced in Guatemala is sidelined."

Against this Spanish-dominated educational system, deliberately amnesiac of the civil war, ideas circulated within the FNE to create an educational center. An autonomous Maya educational center. With intercultural education methodologies. A space where bilingualism was welcome. Historical memory as a pedagogical axis.

With these ideas, in 2003, they shaped the new educational project of the FNE: the Centro Educativo Nueva Esperanza (CECBI).

Beginnings of the CECBI

As with the FNE, the educational center faced difficulties in consolidating as an educational institution. The Ministry of Education did not officially recognize it. They found the pedagogy and methods of the new educational center to be of lesser value and out of place, intending to speak Achi, reclaim the Maya worldview, and teach what truly happened in the civil war.

Therefore, at first, it functioned as an extension of Talita Kumi, an official educational center. For three years, they worked on basic programs in its facilities located in San Pedro Carchá. Meanwhile, with plans to establish the educational center in its own space, the FNE purchased land where, with the help of students and their parents and without any state support, they built the first classrooms and a soccer field.

It was not until 2006, after finally processing the bureaucratic procedure at the MINEDUC, that the Centro Educativo Comunitario Bilingüe Cultural Nueva Esperanza, better known as CECBI, was officially established.

Later, they would achieve a fundamental alliance with a Canadian partner. Assistance came in various ways. For example, it played an important role in the official authorization at the MINEDUC.

Another even more significant help was that, thanks to the partner, the CECBI team met, as if fate had arranged the encounter, a pedagogy that would fit with the philosophy of the educational center and the FNE.

Practice, identity, and memory: the intercultural pedagogy of the CECBI

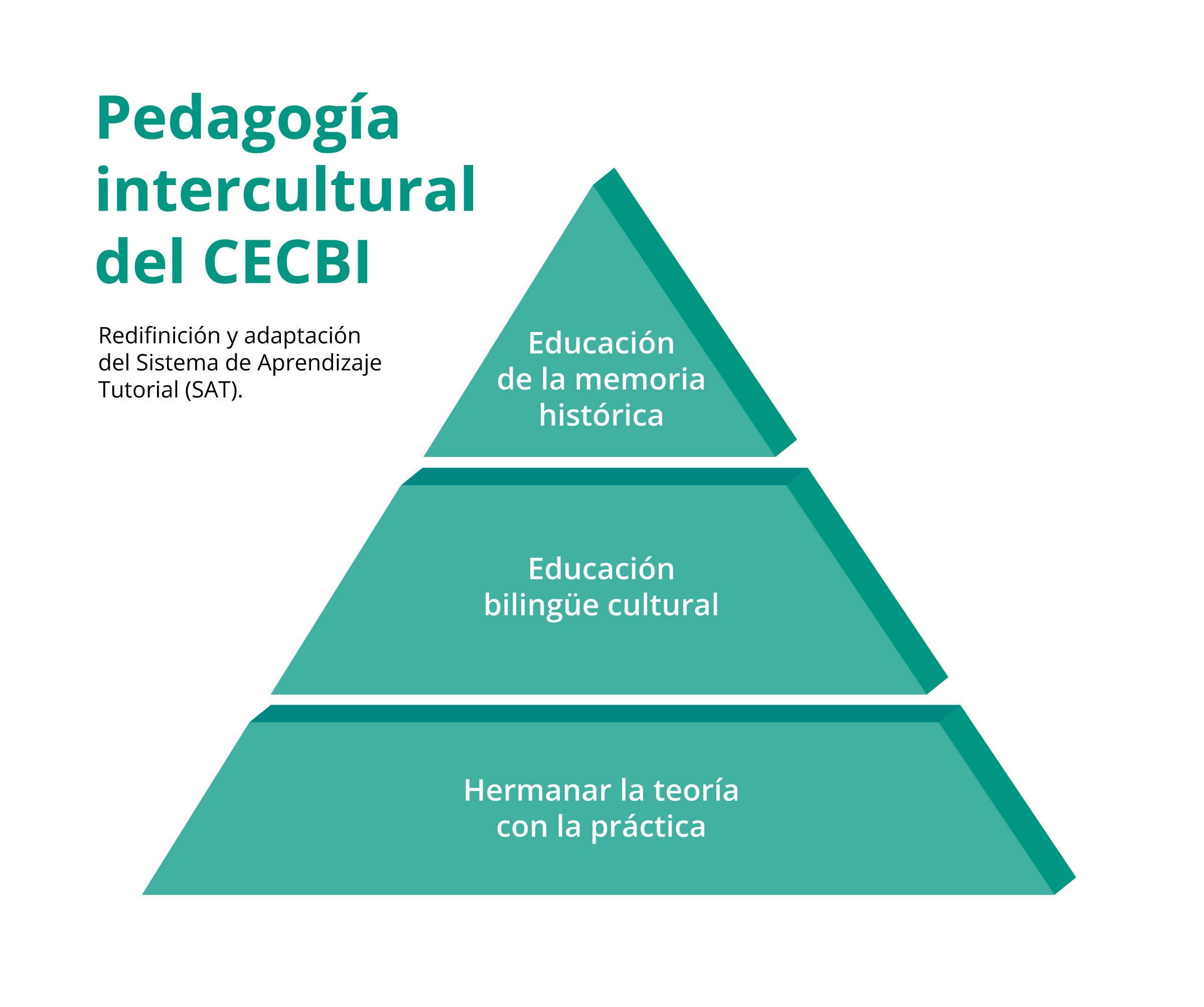

The physical hosting provided by Talita Kumi for three years to CECBI allowed them to closely observe a different methodology.

It was a pedagogy influenced by popular education, oriented towards horizontality and active participation, with a strong focus on agricultural practice. This was reasonable, as it was designed for rural contexts. The methodology is named the Tutorial Learning System (SAT), originated by FUNDAEC in Colombia.

Attracted by the educational potential of the SAT, the CECBI team decided to apply for training with FUNDAEC. The idea was not only to learn the new methodology. They were aware that every cultural context is different. Therefore, they wanted to redefine and adapt the SAT to their own pedagogy: an intercultural one suitable for the Rabinal context and the Achi people.

To educate is to practice

One of the pedagogical axes of the CECBI is to marry theory with practice, which is the foundation of the SAT. The representative example of this principle is reflected in its career in community development7. The career began in mid-2012, as an option for those who wanted to continue studying after finishing the basics. The career also allows students to opt for continuing at universities in the country.

In the career, students learn, over the course of three years, content and subjects about land cultivation, agricultural experimentation, animal husbandry, among others. Parallel to the theoretical learning, in the gardens and crops of CECBI, students put into practice what they have learned in class. Although secondary students also receive practical learning, in high school they delve fully into specialized content.

"As a stone in the path of educational work, we have to respond and force ourselves to the educational policy and the national education plan. Even though we are private, we cannot detach ourselves. So, what makes us unique is projecting an active, participative methodology, where there is a practical area. This practice is seen in two moments: 1) from when the student arrives, and 2) their improved practice, already in the realization of their work, for example, if it involved a plot. That makes us different."

Thus, it is a pendulum learning: from theory to practice and vice versa. Moreover, at the center of learning is the cultivation and knowledge of the land. In the Maya worldview, this is a fundamental issue, but little understood or deliberately stripped by the state aligned with developmentalist and extractivist policies. Moreover, there is another disadvantage: the education of the land and agriculture is belittled compared to other professions and liberal, Western, and urban knowledge.

To educate is to be

The adoption of the SAT (Tutorial Learning System) has been fundamental for the CECBI. However, it has not been an unadopted integration of the Achi Maya culture. They are aware that there can be no comprehensive education without recognizing identity: that is, what it implies and represents to be Achi. It is this particularity of the CECBI that makes its pedagogy, necessarily and committedly, intercultural.

It is worth remembering that the FNE was born in the context of the Peace Accords. At that time, the presence and political efforts of the Maya movement had contributions that influenced the negotiations and planning of post-war education. One of those contributions, perhaps the most important, was the model of bilingual intercultural education (EBI).

From the outset, CECBI has operated under the EBI (Bilingual Intercultural Education) framework. In a country where national education often erases or lacks the capacity to address cultural differences, it was non-negotiable and inevitable for CECBI to provide an education rooted in Maya Achi culture. It’s worth noting that this approach is also a political stance, serving as a decolonial response to a homogenized and Spanish-dominated education system.

Although the Achi language predominates in Rabinal, there are also Ladino youths. CECBI serves students from Rabinal and, as it has grown, from neighboring municipalities. Therefore, language is crucial at CECBI. Speaking both Achi and Spanish caters to Rabinal’s linguistic diversity. On any given day, classes proceed with tutors and students interacting in both Achi and Spanish.

However, EBI encompasses the entire culture, not just the linguistic aspect. Over the years, CECBI has incorporated traditional dances, handicraft production, and the crafting of textiles for Maya garments into its curriculum, among other cultural elements. This cultural inclusion is closely related to the SAT, whose pedagogical practice is connected with the land.

Culture relates to the daily activities we perform. For instance, in the area of productive processes, students learn according to the cultural practices of our ancestors. When it is winter, or when tilling the soil, permission must be sought from the Ajaw. In this case, students must also be familiar with and learn about the nahuales of each day.

If practical learning is in the hands of CECBI’s pedagogy, then the bilingual cultural education model is its heart.

To educate is to remember

CECBI's history is deeply rooted in the Maya experience of the internal armed conflict. From a quest for justice for the massacres arose the FNE and the educational center. Though that dark era may seem distant, education about the historical memory of a period whose tragic legacy still persists today is indispensable at CECBI.

Especially in a country that does everything possible to censor and ignore the Maya genocide, historical memory holds a special place at CECBI. Memory, then, is the Maya resistance of historical truth against the state policy of forgetting.

The historical memory curriculum includes tours of massacred communities, testimonies from survivors, and the commemoration of mournful dates. It is framed within the EBI model, as memory also forms part of cultural identity; in this case, Maya Achi.

"There is classroom participation for commemorations. Students must also travel to the locations; to learn, narrate, and see for themselves. For example, when discussing the commemoration of Xococ on February 13th, students must visit the site. Within the classroom, the religious beliefs of each student are respected because there are students who choose not to participate, but sensitization is key. They cannot be detached from the activities; they must engage."

A notable aspect of historical memory is its method of intergenerational transmission. Firstly, the tours and testimonies are physical and oral traces of Rabinal's and the Achi people's history that students learn. It's a transmission meant to preserve community memory from one generation to the next.

A second form is the intergenerational sequence among students. For instance, in tours and testimonies, students from advanced grades participate in teaching the younger ones. Thus, it's a sequential teaching method: from tutor to student, from student to student. Therefore, tutors are not the only ones with the authority to keep a community memory alive.

At CECBI, this sequence is distinctively horizontal and intercultural. It is not limited to the historical memory curriculum but is a constant pedagogical element throughout CECBI's education: from SAT fieldwork to teaching traditional dances or subjects from the official curriculum.

CECBI in pandemic times

After a long history of innovative projects, diverse methodologies, and unwavering resistance against the lack of state action and attention, by 2020 CECBI had become a reputable organization in Rabinal. Its institutional and pedagogical growth never ceased.

However, in that same year, the COVID-19 pandemic engulfed the world. Remote work, locked-down homes, and empty schools became part of the pandemic landscape. In countries like Guatemala, education inevitably suffered a historic setback, the effects of which are beginning to emerge, despite not fully understanding the economic, cultural, and social scope.

Like many other schools and educational centers, the COVID-19 pandemic interrupted CECBI's educational trajectory. Nevertheless, with their commitment to youth and education, they adapted to the atypical pandemic reality.

Teaching during the pandemic

The week the Guatemalan government decreed health measures and a national quarantine, the CECBI team was returning from an educational excursion. Confused and surprised, they found empty streets and a heavy silence enveloping Rabinal. Similarly, the COVID-19 pandemic abruptly constrained CECBI’s activities.

The team quickly implemented improvised methodologies to address their students' education in an isolation context. They adopted a virtual modality, relying on the internet to share exercises and content, deliver classes, and open spaces for reinforcement and query resolution.

However, in a country with limited infrastructure and technological access, not everyone has internet services or devices, especially those living in rural areas. Therefore, the team decided to conduct weekly visit rounds or monitoring to deliver guides and worksheets. By this time, CECBI had a roster of students from municipalities and communities outside Rabinal. The team organized as best they could to serve students from distant places.

Resuming the virtual modality, they mostly worked with the youth, but not all had internet access to receive classes. They prioritized content in essential areas. When colleagues were not out monitoring, they prepared guides to send to students. Each teacher saw how to transfer content, especially in mathematics, creating tutorials and worksheets. For example, for those without a device, taking the time to explain how to solve problems was crucial.

Another urgent adaptation was related to practical learning; that is, the processes of enhanced practice with crops, gardens, and animal husbandry. With necessary precautions, they summoned small groups of students to the educational center, where they worked on these practices.

Despite considerable efforts to leave no one behind or halt CECBI's educational process, they faced inevitable consequences of the pandemic, beyond the team's control.

Against the pandemic legacy

One of the most notable negative consequences was student dropout due to economic necessity, often with parents' consent. While there had been many cases of dropout since 2015 due to migration or work, the pandemic exacerbated these causes. The CECBI team lamented this situation, as there was little they could do to prevent it.

Upon returning to post-pandemic classes, they encountered difficulties with student attention and learning. First, the ineffective transition between virtual and face-to-face models was evident. As students adjusted to the virtual dynamic, they expected teaching to occur online or placed little importance on face-to-face learning. At CECBI, it became necessary, as one tutor said, "to teach being in school before teaching the content."

Second, the overuse of cellphones led to distraction and inattention among students. Virtuality fostered dependency on the internet and cellphones. Given the limited supervision that remote and screen-based education allowed, and the unavailability of parents for various reasons, students used cellphones and the internet for play rather than learning or doing homework. These difficulties led the CECBI team to identify a decline in student learning.

Last year I taught first grade. It was a challenge because the students were accustomed to the guides. They came from sixth grade, but they were in the mindset of fifth graders. They lacked basic levels of reading comprehension, spelling, and handwriting. We spent until mid-morning reading and doing the exercises to immerse them in face-to-face learning. They were used to doing just a couple of tasks. We have logic games, and we've tried to implement them because it's hard to bring them back.

Another pandemic issue was the emotional toll on students. The CECBI team observed significant socialization difficulties. Students felt isolated, lacking confidence and self-esteem, and quiet as if the quarantine had not yet been lifted. To address this, CECBI initiated vocalization exercises and artistic and playful activities to break the silence and ice among students.

Lastly, regarding the learning of historical memory, social distancing and health measures abruptly cut off commemorative activities, field trips, and the practices of Achi culture. This interrupted the intergenerational sequence. Not only by failing to conduct the content and exercises, but it also broke the teaching cycle of tutor-student, student-student, and disrupted the roles typically learned and taught from CECBI’s intercultural pedagogy.

Beyond the pandemic

In 2023, classes fully resumed. The future remains uncertain in terms of pandemic effects; we are still in the dark about the long-term scope. However, at CECBI, there is a future beyond the pandemic.

Navigating the pandemic in a state of educational emergency has not been easy for CECBI. However, step by step, they have been reclaiming the education they began two decades ago. The presence and work of organizations like CECBI is critically important due to their unique intercultural, identity, and political nature in a country that has historically denied and even systematically annihilated it.

At CECBI, with a firm belief in intercultural education, they hope to establish, through the FNE, a Maya Achi university. The university system, where enrollment is synonymous with privilege for the few who achieve it, has shared the history of national education marked by racism and exclusion against indigenous peoples. The FNE's dream is to replicate CECBI's consolidated work at the university level.

Let us not forget that CECBI's history is that of a people who have resisted and overcome social injustice, the politics of educational ignorance, and the genocide of the Guatemalan state. A history rooted in the practice, culture, and memory of the Maya Achi people.

For CECBI, without interculturality, there is no fair country or true future.

Notes

General notes

This product was designed, visualized and written by the Population Council Guatemala team, with collaboration and feedback from the CECBI team, for the project Recovering Education in Central America: Activating Networks and Associated Groups (RECARGA).

The images presented were taken from CECBI's social networks, shared by its team or photographed by the Population Council Guatemala team. In external cases, the source was indicated.

Specific notes

1. The Conflicto Armado Interno or civil war in Guatemala began, according to the historiographic consensus, in 1960. In 1954 the military forces, sponsored by the United States CIA and allied with the social elites of the time, overthrew the government of Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán, which put an end to the so-called Democratic Spring (1944-1954).

2. The Commission for Historical Clarification (CEH) was established on June 23, 1994 to "clarify with all objectivity, equity and impartiality the violations of human rights and the acts of violence that caused suffering to the Guatemalan population, linked to the confrontation armed".

3. As described by the Academy of Mayan Languages of Guatemala (2012), the name Rabinal and its meaning show vestiges of these first inhabitants. Rabinal means "place of the lord's daughter", derived from the Q'eqchi' language with the components: rab'in (lord's daughter) and the locative al. The meaning of the name alludes to an ancient myth about the Old God of the Earth who, as the owner of the hill, lived in a cave. In that palace, along with all the animals, he kept his most precious treasure: his daughter, who was called Po (which in the Q'eqchi' language means "moon"). The myth tells how a young hunter, named B'alan Q'e (which is also a Q'eqchi' word, meaning "hidden sun") went to the cave daily and watched Po weaving. Disguised as a sparrow, B'alan Q'e manages to enter the cave and after spending the night together, escapes with Po. When the Old God of the Earth discovered that they had fled, his anger knew no bounds and he called his brother, the God of Rain, to pursue them. After several adventures, the couple finally obtained the consent of the Old God of the land to marry and then B'alan Q'e became a sun, while Po rose as a moon. At that moment the present epoch is created.

4. A dramatic dance, cataloged in 2008 as Intangible Heritage of Humanity, which stages, with theater and music, the power conflicts between the K'iche' confederation, from which the Rabinaleb are freed to form their own people.

5. In 1999, the population voted “No” in the popular consultation that would give way to the Agreements acquiring constitutional status and that would allow compliance with their content. Conservative groups were leaning towards this result, arguing that the approval of the reforms would favor the polarization of the country and would privilege indigenous peoples... a sector that has historically been marginalized and excluded, and whose living conditions tend to be precarious. The result of the consultation prevented strong mechanisms from being put in place to comply with the Agreements.

6. On October 26, 2023, the Population Council team held a participatory workshop, lasting six hours, at CECBI. 8 people from the CECBI team participated.

The objectives of the workshop were, through a guided group discussion and timeline, to a) collect the local history of Rabinal, b) document the organizational and educational development of CECBI, especially during and after the pandemic, and c) understand the ecosystem educational institution in which the partner is located.

One of the products was this case study in the form of a narrative history, prepared after a process of systematization of the workshop, bibliographic review, statistics, audiovisual archive and interview.

7. At first they appointed her as an expert in rural welfare. However, the MINEDUC opposed the title. Therefore, they had to rename her as a community development expert so that she could fit into the careers of the official MINEDUC portfolio. At CECBI, however, they continue to call it rural well-being, as it is a fairer name in relation to their worldview of land and education.

Bibliography

Academia de Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala. (2012). Retaliil ano’nib’al mayab’ achi. Monografía Maya Achi. https://www.almg.org.gt/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/MONOGRAF%C3%8DA.pdf

Ajcalón Choy, R. (2017). Luchas indígenas en Cubulco y Rabinal, Baja Verapaz, Guatemala, en el contexto del multiculturalismo neoliberal. LasaForum, 48(2), 28.

Arnauld, M.-C. (1993). Los territorios políticos de las cuencas de Salamá, Rabinal y Cubulco en el Postclásico (Baja Verapaz, Guatemala). En Representaciones del espacio político en las tierras altas de Guatemala: Estudio pluridisciplinario en las cuencas des Quiché oriental y de Baja Verapaz. (pp. 43–109). Centro de estudios mexicanos y centroamericanos. https://books.openedition.org/cemca/2386?lang=es

Calveiro, P. (2006). Los usos políticos de la memoria. En Sujetos sociales y nuevas formas de protesta en la historia reciente de América Latina. Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales [CLACSO].

Concejo Municipal de Rabinal, Baja Verapaz. (2019). Plan de Desarrollo Municipal y Ordenamiento Territorial, municipio de Rabinal, Baja Verapaz 2019—2032.

Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos. (2012). Ficha Técnica: Masacres de Río Negro Vs. Guatemala. Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos. https://www.corteidh.or.cr/CF/jurisprudencia2/ficha_tecnica.cfm?nId_Ficha=224

Cujá Jerónimo, M. A. (2008). Actitud de los docentes bilingües (achí—Castellano) hacia el sistema de la educación bilingüe intercultural de Rabinal, Baja Verapaz [Licenciatura]. Universidad Rafael Landívar.

Cumes Simón, A. E. (2004). Interculturalidad y racismo: El caso de la Escuela Pedro Molina, en Chimaltenango, Guatemala [Maestría, Guatemala: FLACSO, Sede Guatemala]. http://repositorio.flacsoandes.edu.ec/handle/10469/1844

Dávila Díaz, S. G. (2019). Proceso danzario en Rabinal: Cambio y continuidad en un municipio maya achi [Licenciatura]. Universidad del Valle de Guatemala.

De Gamboa Tapias, C. (2019). La Memoria Como Política Y Las Responsabilidades Derivadas Del Pasado. Ideas y Valores, LXVIII(5), 81–104.

DIGEBI. (n.d.). Dirección General de Educación Bilingüe Intercultural. DIGEBI. https://digebi.mineduc.gob.gt/digebi/

Environmental Defender Law Center. (n.d.). La Represa Chixoy y las Masacres de Río Negro. https://edlc.org/es/cases/fighting-human-rights-abuses/the-chixoy-dam-and-the-rio-negro-massacres/

Escalón, S. (2019). Guatemala: De cómo unos campesinos de Rabinal vencieron la sequía. https://nomada.gt/identidades/guatemala-rural/guatemala-de-como-unos-campesinos-de-rabinal-vencieron-la-sequia/

Gordillo, P. (2013). Comprendiendo la violencia estructural en Guatemala. Brújula. https://brujula.com.gt/comprendiendo-la-violencia-estructural-en-guatemala/

Guerrero Garnica, J. M. (2013). Violencia estructural en Guatemala o la institucionalización de la violencia. Analistas Independientes de Guatemala. https://www.analistasindependientes.org/2013/05/violencia-estructural-en-guatemala-o-la.html

Hemeroteca PL. (2016, May 12). Triunfa el “No” en consulta popular de 1999. https://www.prensalibre.com/hemeroteca/triunfa-el-no-en-consulta-sobre-acuerdos-de-paz/

Henríquez Puentes, P. (2007). TEATRO MAYA: RABINAL ACHÍ O DANZA DEL TUN. Revista Chilena de Literatura, 70, 79–108. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-22952007000100004

Instituto Nacional de Estadística Guatemala. (2018). XII Censo Nacional de Población y VII de Vivienda.

Kupprat, F. A. (2011). Memorar la cultura: Modos de mantener y formar las identidades mayas modernas. Estudios de Cultura Maya, 38, 145–166. https://doi.org/10.19130/iifl.ecm.2011.38.53

La Parra, D., & Tortosa, J. M. (2003). Violencia estructural: Una ilustración del concepto. Documentación Social, 131, 57–72.

Martínez Paiz, H. (2009). LA METAMORFOSIS DE UNA COMUNIDAD ACHI: EL CASO DE RÍO NEGRO-PACUX. XXII Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 2008, 285–295.

Méndez Reyes, J. (2012). Descolonización del saber. Una mirada desde las Epistemologías del Sur.

Mosquera Saravia, M. T. (2018). Informe final sobre la posesión ancestral de las comunidades Chitucán, Canchún, Mangales y Río Negro de Rabinal, Baja Verapaz. Guatemala: Secretaría de Asuntos Agrarios de la Presidencia, Gobierno de la República de Guatemala. https://ceur.usac.edu.gt/pdf/OPA/[MTMS]Informe_Peritaje_Cultural.pdf

Prensa Comunitaria. (2020). Las masacres del Río Negro. Prensa Comunitaria. https://prensacomunitaria.org/2020/02/las-masacres-del-rio-negro/

Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo (PNUD). (2022). Desafíos y oportunidades para Guatemala: Hacia una agenda de futuro. La celeridad del cambio, una mirada territorial del desarrollo humano 2002—2019 (p. 424).

Sáenz de Tejada, R. (2022, January 17). Guatemala: ¿25 años de paz? Nueva Sociedad. https://nuso.org/articulo/guatemala-25-anos-de-paz/

Sam Colop, L., & Sandoval, M. C. (2012). La educación bilingüe intercultural en Guatemala: Análisis de las propuestas curriculares y las prácticas en escuelas públicas [Maestría, Universidad de Antioquia]. https://bibliotecadigital.udea.edu.co/dspace/bitstream/10495/7107/1/LidiaSam_2012_educacionguatemala.pdf

Sieder, R. (2008). Entre la multiculturalización y las reivindicaciones identitarias: Construyendo ciudadanía étnica y autoridad indígena en Guatemala. En Multiculturalismo y futuro en Guatemala (pp. 69–96). FLACSO/OXFAM.

Torres Ávila, J. (2013). La memoria histórica y las víctimas. Jurídicas, 10(2), 144–166.

Viceministerio de Educación Bilingüe Intercultural. (2009). Modelo Educativo Bilingüe e Intercultural. Ministerio de Educación.

Wikipedia. (2023, diciembre 27). En Wikipedia. https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jesús_Tecú_Osorio